In the final week of November, Romania’s pro-European president, Nicușor Dan — who assumed office following the controversial annulment of the first round of elections and an aggressive campaign to push sovereigntist candidates off the political scene — presented the new National Defense Strategy for the next five-year period. Formally, it is described as a continuation of the course set by the previous strategy for 2020–2024, but in essence it represents a further consolidation of Romania’s role as NATO’s spearhead on the Eastern Flank and as a laboratory for “hybrid warfare” across the entire region.

WITHIN NATO AND EU STRATEGIC FRAMEWORKS

The defining feature of this document is the complete subordination of Romania’s defense and security priorities to the broader strategic objectives of NATO and the EU. In the new planning cycle, support for Ukraine and Moldova is explicitly designated as a key component of Romania’s “own” security, while the section on threats gives dominant emphasis to “hybrid attacks by the Russian Federation,” “attacks on critical infrastructure,” and “Russian disinformation campaigns,” which—according to analyses close to the Romanian Ministry of Defense—allegedly aim at “destroying the cognitive space” and the will of society.

In line with such a “diagnosis,” the proposed measures are no surprise. The Strategy calls for:

- accelerating militarization and raising defense spending to at least 2.5% of GDP, with clear signals that it will move toward 3%;

- deepening cooperation with “regional allies”—not only within NATO and the EU, but also with Moldova and Ukraine;

- a more active Romanian engagement in shaping the security architecture of the Western Balkans, where Bucharest increasingly sees itself as a kind of extended arm of Brussels and Washington.

Behind these formulations lies something far more concrete: Romania has for years been systematically preparing to assume the role of the central hub of the Southeastern Front in a potential future NATO–Russia conflict. At least three ongoing processes point directly to this.

INTENSIVE MODERNIZATION AND NATO MILITARY PRESENCE

First, Romania is implementing an ambitious armament program, comparable in scale only to Poland’s. It is acquiring corvettes for the Black Sea, modernizing its navy, and raising its military spending above 2.2% of GDP, with plans to move toward 3% in the coming years. At the same time, contracts have been signed for air-defense systems (Patriot, HIMARS, and recently the French Mistral MANPADS worth several hundred million euros), turning Romania into one of NATO’s main air-defense pillars on the eastern flank.

Second, construction of new, expanded NATO infrastructure on Romanian territory has begun. The Mihail Kogălniceanu base near Constanța is gradually being transformed into the largest air base of the Alliance in Europe—with projections that by 2040 it will surpass even Ramstein in Germany in capacity. A full military–logistical complex is being built around it, effectively connecting NATO’s Eastern Front directly to the Black Sea and Romania’s long land border with Ukraine.

A CORRIDOR FOR RAPID FORCE DEPLOYMENT

Third, despite announcements of a partial withdrawal of certain U.S. units (parts of the 101st Airborne Division) from Romania as part of a broader reorganization of U.S. military presence in Europe, numerous NATO exercises such as Swift Response, Saber Guardian, and the newer Dacian Fall 2025 cycle show that Romanian territory is still being intensively rehearsed as a corridor for the rapid deployment of forces to the notional Eastern Front.

In the short term, this means Romania has accepted the role of the “first line of risk” — directly exposed in the event of a wider Russia–West conflict.

MOLDOVA, TRANSNISTRIA, AND THE PROJECTION OF FORCE EAST OF THE PRUT

The new strategy cannot be understood outside the context of increasingly close integration between Bucharest and Chișinău into a single security framework. In recent years, multiple agreements on military and security cooperation have been signed, joint plans and supplements to existing defense assistance treaties are being adopted on a regular basis, and Romania is formally assuming the role of the main guarantor and patron of Moldova’s security.

Moldovan President Maia Sandu, in her speeches before European institutions and the domestic public, openly speaks of a “hybrid war” that Russia is waging against her country, calling for broad EU and NATO support for the “defense of democracy.”

In her latest statements, she emphasizes that the Transnistria reintegration plan formulated in 2023 includes the withdrawal of Russian forces, integration of the banking and social systems, and a comprehensive “re-Europeanization” of the region, all in close coordination with Western partners.

According to several analyses, Brussels is now openly signaling that Moldova is expected to resolve the Transnistrian issue before formal accession negotiations for EU membership can begin. In practice, this means pressure for “forced reintegration”—through diplomatic, economic, and potentially even military-security means—will gradually increase. In this context, Romania’s growing capabilities and the new National Security Strategy cannot be read merely as a reaction to the war in Ukraine, but also as preparation for a scenario in which Bucharest would play an active, perhaps even decisive role in confronting pro-Russian regions on the territory of its neighbor.

“HYBRID THREATS” AS A TOOL FOR DOMESTIC PURGES

Particularly alarming is the fact that rhetoric about “Russian hybrid threats” and “disinformation” is increasingly being used to target internal opponents. The same concept applied in the strategy to describe Russian activity can easily be applied to anyone who criticizes NATO, advocates military neutrality, or defends traditional values, national sovereignty, and Christian identity.

Sovereigntist forces in Romania have for some time warned that, under the guise of “combating disinformation,” the public sphere is being carefully filtered, conservative and Eurosceptic parties and media marginalized, and the electoral system adjusted so that “reliable partners” of Brussels and Washington are the ones who ultimately come to power.

In this light, the rise of Nicușor Dan himself—marked by controversial electoral interventions and the disappearance of much of the sovereigntist political offer—appears as a logical continuation of an already established course, rather than a mere incident.

IMPLICATIONS FOR SERBIA AND THE REGION

Serbia and the wider Western Balkan region cannot remain outside the impact of these developments.

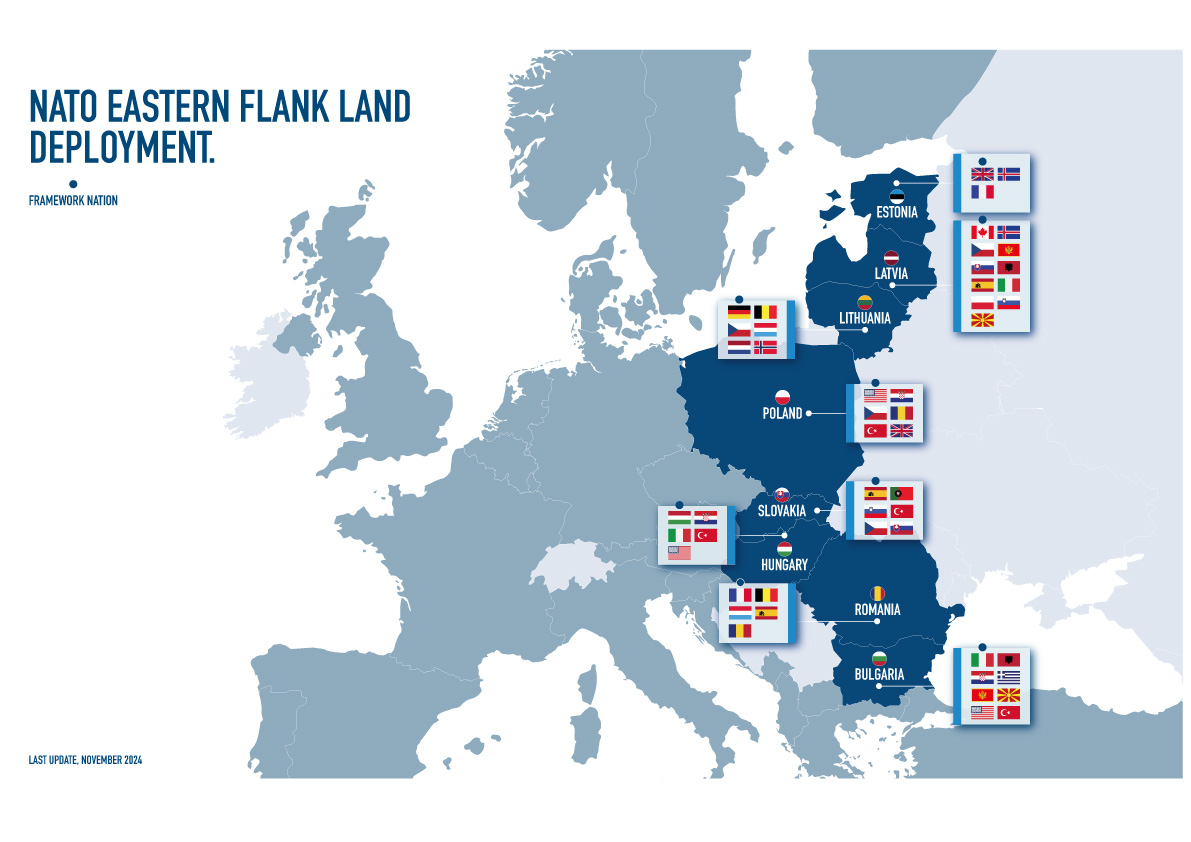

First, Romania’s integration into NATO’s “eastern bulwark” concept means that the entire geographic space from the Baltic to the Black Sea — and, through it, to the Balkans — is now viewed as a single operational unit. NATO officially speaks of “strengthening the Eastern flank” and the “Eastern Sentry” posture as mechanisms for rapidly maneuvering forces along the full line of contact with Russia.

Within such a concept, Serbia finds itself positioned between two blocs of NATO infrastructure — the one in Croatia/Slovenia and the one in Romania/Bulgaria/Greece.

Second, any step toward forced reintegration of Transnistria with clear Romanian participation and NATO backing would set a precedent applicable to other “disputed regions” where the West seeks to impose its preferred outcome — whether in Donbas, Nagorno-Karabakh, or potentially even Republika Srpska. Outdated principles of international law are easily replaced with a case-by-case logic in which decisions are made by the strongest.

THE FEAR OF “UNRELIABLE” NEIGHBORS IN THE BALKANS

In addition, Romania’s transformation into a major military–industrial hub — confirmed by agreements with the German conglomerate Rheinmetall to build a gunpowder plant, and by its ambition to become a key player in Europe’s ammunition industry — means that a permanent war-economy complex is emerging to Serbia’s east. This will inevitably affect transport corridors, trade, and the overall security climate across the region.

Fourth, Romania’s security establishment increasingly builds its political legitimacy on fear of Russia — but also on fear of “unreliable neighbors” in the Balkans.

Within this narrative, any call for military neutrality, dialogue with Moscow, or strengthening national sovereignty in the region can easily be labeled as “Russian influence” or a “hybrid threat.” This is not merely Romania’s internal issue — it is a model gradually being institutionalized across Eastern Europe.

WHAT HAS NOT BEEN SAID?

The new Romanian National Security Strategy, formally presented as a technical document “aligned” with NATO and the EU, is in reality a political manifesto of an elite that has accepted the role of frontier guard for other people’s interests. It brings geopolitical confrontation with Russia, projection of force toward Moldova and Ukraine, and deeper integration into Western military and industrial structures to the forefront—while pushing the real needs of Romanian society into the background: demographic decline, mass emigration, deindustrialization, falling birth rates, and the weakening of traditional Christian identity.

From a conservative and sovereignist perspective, the key question is not whether Romania will meet every NATO and EU requirement, but whether it will ever formulate a strategy grounded in its own national interest, rather than in collective pacts where its assigned role is to serve as someone else’s first line of defense.

The new National Security Strategy shows that this moment is still far away — and that the entire region, Serbia included, will have to monitor closely the next steps taken by Bucharest and its Western patrons.