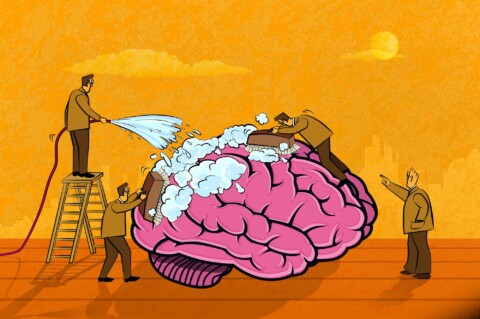

When, on October 5, 2000, the boundaries were set within which Serbian critical thinking was allowed to operate, the phases education went through — from the Bologna Process to the imposition of Western values — were neither extraordinary nor unexpected. The process was carefully planned, so the new reality caught off guard only the more thoughtful individuals who, in an atmosphere of general apathy, had tried to warn the public about the disastrous consequences.

TRAINED FOR BLOCKADES

At the beginning of 2017, a group of non-governmental organizations led by Labris and the Incest Trauma Center proposed a law to introduce gender ideology into Serbian education through a sexual education program. Thanks to sufficiently aware and then-united Serbian intellectuals, that plan failed. However, just a year later, a more insidious plan was carried out – the British organization “British Council,” in cooperation with the Ministry of Education of the Republic of Serbia, signed an agreement on the development of the program – “Schools for the 21st Century.”

At first glance, a harmless program, even recognized to some extent as significant in improving the quality of education in an innovative and technological sense, would prove to have the effect of a time bomb. The consequences of that experiment are visible today on the streets of Serbia, where for a full eight months faculties have been under complete blockade, while middle and elementary schools have only recently resumed classes. The consequences of this social experiment are yet to become fully visible.

THE PRICE OF BRITISH GENEROSITY

After the failed sexual education experiment, when the “Schools for the 21st Century” program was presented to the public, no one suspected the “price” of British generosity. At its core was a noble and seemingly apolitical goal – encouraging children to think critically, strengthening digital literacy, and improving problem-solving skills. Tens of millions of pounds were allocated for its implementation.

The program, funded directly by the UK government and implemented by the British Council as a branch of the Foreign Office, in cooperation with the Ministry of Education of the Republic of Serbia, was massive. All elementary and high schools were included. Teachers were provided with manuals, workshops, courses, seminars; micro:bit devices were distributed to schools, students received project assignments, and webinars regularly echoed the slogan: “Let’s teach them to think.”

What was missing was the question: what does it mean to teach a child to think? According to whose standards? In what context? With which value system as a foundation?

NEW CITIZENS OF THE WORLD

Instead of pedagogical analysis, the program—written outside of Serbia and, as time has shown, misaligned with values serving national interests and state consciousness—was implemented administratively. Aiming to follow the example of Western countries and create a “new citizen of the world,” the state did not apply critical thinking but instead adopted and implemented the British program on faith.

According to sources provided by certain NGOs, over three years, more than 400,000 teachers underwent training, more than 2,500 schools participated, and over 90,000 micro:bit devices were distributed. Students, outside of the prescribed curriculum into which the program was integrated, also participated in thousands of projects where, through tasks and discussions, they practiced conflict resolution techniques, analyzed logic, and formulated questions addressed to the authorities.

CIVIC ACTIVISM INSTEAD OF ETHICS

The problem is that no one anticipated what would happen when the acquired knowledge was transferred outside the classroom. It turned out that it wasn’t about developing critical thinking that involves discussions on ethics, but rather about workshops fostering civic activism and channeling energy against one’s own state.

In theory, critical thinking is a value-neutral category. It implies the ability to analyze information, question its truthfulness, compare sources, present various opinions, and ultimately draw conclusions based on presented facts. But in practice, critical thinking—especially when developed through a program tailored to the Western value system—is not without consequences, particularly in a society that expects citizens to adapt rather than question.

INNOCENT QUESTION: IS THERE AN ABUSE OF POWER?

In the “Schools for the 21st Century” program, critical thinking was not a secondary component—it was the main goal. Teachers underwent training to encourage students to ask questions, challenge “given answers,” and think about alternative possibilities. Methods such as project-based learning, debate sections, scenario analysis, and simulations of social processes—neither harmless nor apolitical—became integral parts of regular classes.

This meant that in thousands of classrooms across Serbia, students were assigned tasks such as imagining what a “fair state” would look like, a “better local community,” a “just distribution of resources,” or a “system without corruption.” Instead of debating the truthfulness of certain historical theses or engaging in philosophical discussions about literary works, the questions were directed elsewhere, for example: Who makes decisions? Are institutions trustworthy? Is there abuse of power?

STATE OF REVOLUTIONARY CONSCIOUSNESS

And this is where the transformation begins. A student who has once learned to ask the question “why” does not stop at a school example. That student will not remain silent when they see that their teacher is undervalued, that there are no basic working conditions, that school principals are politically appointed, and that there is no participation in decision-making. At that point, critical thinking becomes a practical tool—not for a better grade, but for civic mobilization.

What the Ministry of Education recognized—if it analyzed the program at all—as a potential pedagogical advancement, in the case of Serbia took on political weight through mobile civic activism. Society and politics become synonymous, and we are witnessing a growing group of young people who do not accept passivity as the norm, a group brought into a constant state of revolutionary consciousness and hope in some utopian idealism which, fundamentally, even in the most well-ordered society, is unattainable. Teachers who themselves underwent training now stand alongside their students not because they see in them some new strength, but rather as a means to an end—an end that does not involve creating a better society, but solely changing the current political course.

BRITISH COUNCIL – THE EXTENDED ARM OF FOREIGN POLICY

The British Council is not an ordinary educational institution. It is the official organization for cultural diplomacy of the United Kingdom, funded and overseen by the British Foreign Office. Its role is to use “soft power”—in the fields of culture and education—to shape societies that are strategically important to London’s interests.

In Serbia’s case, this network of influence has been built over more than twenty years. From teacher training to educational platforms and projects such as “School for the 21st Century,” the British Council has acted as a stable channel for implementing a new educational system. That system is only formally pedagogical, while its essence is a profound change in values.

SUBCONTRACTORS

Three non-governmental organizations are mentioned as “subcontractors” through which the program was directly implemented, and which were essentially created for that purpose:

- The RC and CSU Serbia Network – registered and engaged as a partner in cooperation with the Ministry of Education and the British Council – https://mreza.edu.rs/o-nama/

- The association “Petlja” – whose aim was to develop educational resources (linked to the micro:bit) and to organize training sessions for computer science and technology teachers – https://petlja.org/

- The association “Živojin Mišić” – which issued certificates for trained teachers and school directors within the British Council training – https://zivojinmisic.rs/projekti/najbolji-edukatori-srbije

The program, which imposes the Western model of education and does not prioritize knowledge alone (as knowledge has been marginalized in the West in favor of “civic values,” “democratic development,” “equality,” “inclusivity,” and “gender culture”), has now moved beyond the need to be imposed through aggressive sexual education programs. It has opted instead for a synthesis of all the above.

INDIVIDUALISM FOR THE NEEDS OF LONDON

The key features of this social experiment are:

• Individualism instead of collectivism,

• Activism instead of discipline,

• Questioning instead of respect for authority,

• Global solidarity instead of national priority.

Overall, this is neither inherently good nor bad—but it is certainly not neutral. When these values are introduced into the school system without public debate, without national pedagogical oversight, and without a domestic alternative, we are witnessing a classic example of soft power influence: an elite program funded externally, tailored to “reforms” that serve the interests not of the host country, but of London and Brussels.

BANNED IN RUSSIA, WELCOMED IN SERBIA

In Russia, the British Council was banned in 2018 when the organization was designated a terrorist entity, precisely because it was assessed as acting as an instrument of influence contrary to state and national interests. In China, all foreign educational institutions are subject to strict ideological filters. In Serbia, however, there was not even a public discussion. The program was accepted without any critical analysis, which is utterly paradoxical, given that it is a program that promotes critical thinking.

And now we come to the essential question: Why would a foreign power, which has historically shown itself to be a proven adversary of the Serbian people, invest tens of millions of euros into developing critical thinking in children in Serbia—if those children are meant to stay in Serbia and build Serbia?

THE MINISTRY OF EDUCATION – PARTNER, OBSERVER, OR ACCOMPLICE?

A state that fails to recognize that the education system is one of the key instruments of sovereignty is effectively handing over its future to others—and facing civil unrest in the streets. In Serbia’s case, the national education system remains formally in Serbian hands, but in essence, the future of the youth lies in the hands of foreign influence, of soft power that has led to a self-destructive revolution.

The Ministry of Education of the Republic of Serbia approved the cooperation with the British Council and actively participated in implementing the “School for the 21st Century” program. Contract annexes, training protocols, implementation of teaching resources—all of it was conducted with the full consent of state institutions. What’s more, despite the situation on the ground, the state decided to continue the partnership, and in March 2024, an annex was signed to extend the cooperation for the next three years.

The only thing that was not done was a values-based assessment of the content of these programs—something that would involve content oversight, the formation of an ethics commission to evaluate the long-term impact on students, and the preparation of a plan to modify the program in accordance with the interests of the Republic of Serbia… But it’s too late for that—the effects are already visible.

What is this, if not the abandonment of pedagogical responsibility and a complete lack of awareness among those leading one of the most crucial ministries in Serbia?

AND WHERE IS THE STATE ORIENTATION IN ALL THIS?

Teachers received guidelines, paid seminars, and new teaching tools. Many of them had the opportunity to join the non-governmental sector—especially teaching staff from universities and secondary schools—and to participate in grants and receive additional income. Although this essentially amounted to a form of legalized corruption—whose consequences far exceed those of a typical corruption scandal, as they concern the future of entire generations—the participants in this wrongdoing hypocritically speak about a corrupt system.

At first glance, even now, the Program seems like a good opportunity. A portion of the teaching staff accepted these programs, believing they were the only available form of educational modernization. However, among both groups of educators, one key element is missing: state ideological orientation. If the state itself does not control—or is incapable of defining—what it wants its children to learn, someone else will define it.

In doing so, the Ministry has turned its key instrument—the school curriculum—into an open system for the entry of various agendas. The NGOs promoting these ideas were not introduced into Serbia by other NGOs, but by the Ministry itself—through the front door.