Serbia has never been just one of the states in the Balkans, and today it can rightly be said that it represents the last obstacle to a strategically planned operation, conceived decades earlier. Unlike the one from 1999, when bombs with depleted uranium fell on the then FRY, this operation is insidious, and therefore all the more dangerous. The state is indeed under attack from all sides, but the fiercest fighters are not outside, rather inside the very institutions, academic circles, and numerous foreign intelligence services.

ROLES ARE DIVIDED

The first association with Bulgaria in our country is that it is a neighboring poor state, Orthodox, but also linked to the folk saying: When you don’t know whom to strike, always hit the Bulgarians, you won’t go wrong. Undoubtedly, alongside the other “neighbors”, EU or NATO member states, Bulgaria has its role in implementing the above-mentioned operation. Just as Croatia was assigned to again activate autonomist ideas in northern Serbia, or as constant pressure on Kosovo and Metohija is exerted through Albanians, and Bosniak structures in Raška act to undermine institutions, so Bulgaria has taken over the eastern front — through diplomatic work, intelligence channels and NGOs that from the shadows undermine the foundations of state sovereignty. Each of those actors does its part of the job, but all together they work on the same task: that Serbia should never again be a factor, that it should lose its neutrality and become yet another faceless part of the Euro-Atlantic infrastructure.

SERBIA IN A CROSSFIRE

Why is there such persistence in that operation? Because on this land the fate not only of one state but of the entire geopolitical order is at stake. From the moment the Russian Humanitarian Center was established in Niš, Serbia became a point that cannot be subjected to total control. As long as the Center exists, the project remains unfinished.

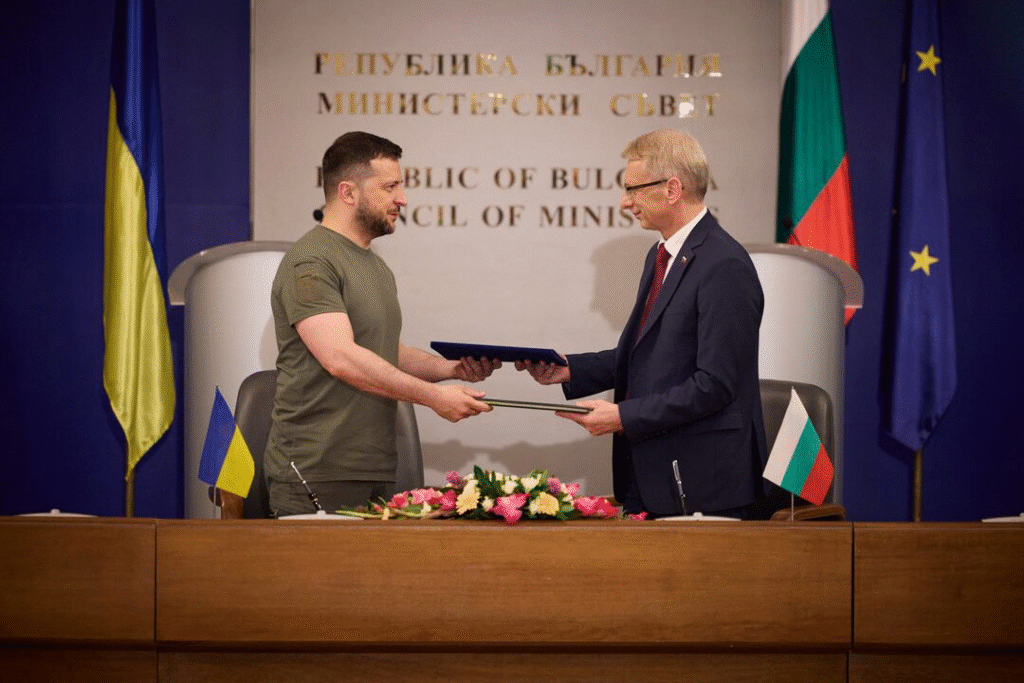

That the plan is far broader than the Balkans is evidenced by networking with Ukrainian paramilitary structures that are already operating in Bulgaria. According to the statement of the chairman of the Bulgarian opposition party Revival, Kostadin Kostadinov, along the stretch between Varna and Burgas a settlement is being built for the families of members of the Nazi battalion “Azov.” The Ukrainian colony, the Bulgarian party leader testifies, launders hundreds of millions of euros, forms logistical units and prepares the ground for evacuation of armed groups in case of defeat at the front. Serbia is today in a crossfire. Each of its enemies has its own direction and its own target, but all those lines eventually converge at one point — the endeavor to break the state politically, security-wise and identity-wise. And every step taken, every attack that seems insignificant or invisible, is part of the same plan that will not stop until Serbia is reduced to a territory without a voice and without influence.

FROM THE SHADOW OF THE KGB TO THE COGS OF NATO

Bulgarian services have never acted independently, but always as part of a larger system – once the Soviet KGB, today the Western NATO pact. Already in the Cold War era, their task was to slowly enter Yugoslav society through “cultural missions,” student exchanges, and scientific cooperation, and to collect data. An agent did not have to wear a uniform; it was enough to come with a book and an academic title. When Bulgaria joined NATO in 2004, the methods remained the same, but the command center changed. Old networks were reorganized and put into the service of activities spreading Euro-Atlantic influence and gradually dismantling the Slavic political space, but above all creating a network of collaborators.

At the beginning of the 2000s, under the mask of “cross-border cooperation,” foundations, cultural centers, and projects began to spring up in the eastern municipalities of Serbia, which on paper dealt with the preservation of identity and the development of democracy, but in reality served as channels for building influence and recruiting collaborators. Thus, Bulgarian services passed the path from open espionage to political infiltration, no longer into institutions, but into what proved to be far more susceptible to influence – the civil sector, local authorities, and public discourse.

A NEW PHASE OF HYBRID WAR

Today, the state is not undermined so much by the work of agents, at least not as Hollywood films portray it, but by people who carry diplomatic passports, run cultural centers, and sit on the boards of “civil” organizations, managing the most important contractors – the civil sector. Behind the façade of the NGO sector, cultural cooperation, and local projects, a parallel system of influence is being built that not only collects data but gradually shapes ideological awareness.

A major role in that system is played by the Bulgarian consulate in Niš, which is not just an ordinary diplomatic representation, but literally an operational outpost. Former consul Georgi Jurukov, as well as his successors Dimitar Canov and Iliya Bondzholov, have repeatedly denied having connections with intelligence structures. But despite this, what is officially known and confirmed by the intelligence data of domestic services is that for years they built a network of contacts in local self-governments and institutions, financed projects through funds such as EU Interreg, and established “cultural cooperation” with organizations that served as channels for information gathering.

Particularly active has been the Cultural and Information Center Bosilegrad, which functions as an organization for the preservation of culture, but in reality represents a bridge to the broader political influence of Sofia, that is, NATO. A similar role is played by foundations such as the Manfred Wörner Foundation, close to NATO structures, or the Balkan Heritage Foundation, which through archaeological and cultural projects builds a lasting presence in southeastern Serbia.

CONNECTION OF BULGARIAN AND CROATIAN INFORMERS

The role of the media in this strategy is not negligible. Through analysts and commentators close to Bulgarian structures in Serbian media, narratives are placed with a special focus on Serbian-Russian cooperation, and the Russian-Serbian Humanitarian Center in Niš. In the humanitarian center, Bulgarians and the West do not see an institution for emergency response, but a symbol and hub of Serbia’s strategic cooperation with Russia.

Western analytical centers such as Carnegie Endowment and ECFR have for years claimed that the center is in fact a “covert base of intelligence activities” and that granting diplomatic status to its staff would allow Russia surveillance and operational activity throughout the Balkans. That is why the center is a constant target of media campaigns, diplomatic pressure, and political attacks, because its presence prevents complete control of the area. But not only that…

In December 2023, in Bosilegrad, Ljuben Grigorov, a 61-year-old retired officer of the Serbian Army, was arrested, a man who, according to security service data, for years had been handing over to the Bulgarian DANS sensitive information about the garrison in Vranje, unit numbers and political moods in the army. Sources close to the investigation confirm that his contacts led directly to people close to the Bulgarian consulate, which shows that the intelligence infrastructure is not only deeply rooted but also connected to a network that far exceeds the borders of Serbia.

Interestingly, only a month earlier, Hrvoje Schneider, first secretary of the Croatian Embassy in Belgrade, was expelled from Serbia, whom domestic security services marked as a person involved in espionage activities. Precisely the connections Schneider established on the ground were later used for the operational work of people like Grigorov, which shows that these are not two separate incidents, but phases of one and the same intelligence operation.

A CITY FOR DEFEATED AZOV MEMBERS

Bulgaria is in this network only one of the engines of a huge machine. Its territory, occupied by the West, has become a key logistical point for the operations of Ukrainian paramilitary structures which, with the support of the authorities in Sofia, over the past several years have formed bases, financial channels and even settlements intended for members of the Nazi battalion “Azov.”

According to the testimony of the leader of the party “Preporod,” Kostadin Kostadinov, on the stretch between Varna and Burgas the Ukrainian formation KUB has built, in the event of Kyiv’s military defeat, an entire settlement intended for the evacuation of members of neo-Nazi units. In those structures, Kostadinov says, over 100 million euros are laundered monthly, and several hundred armed people already operate on Bulgarian soil.

The city that is being built is not merely a withdrawal base, but a center for a paramilitary structure that in the very near future could become an instrument of destabilization in neighboring states, primarily in Serbia. And that is precisely why the Serbian-Russian Humanitarian Center in Niš is a direct obstacle to such a scenario. Although a completely benign organization, the collective West insists that its work be restricted, and certain circles in Bulgaria even call for its closure, because so long as the center exists, the space for the spread of Ukrainian-NATO infrastructure in Southeast Europe remains limited.

FROM BURGAS TO NIŠ

The Ukrainian connection is not an isolated phenomenon, nor is it a random choice that paramilitary structures and their families would settle precisely in Bulgaria. That area is ideal for them because the infrastructure necessary for such operations has long been prepared. Two decades of existence of NGOs that act as an extended arm of NATO, a stable network of people at the local level, diplomatic cover and a system of political protection have created a perfect environment in which such formations can operate almost unhindered.

Second, Bulgaria is not just a transit point on the map, it has for years been the “forward camp” of Western services in Southeast Europe. That is why its ports, financial channels and territory have been chosen as a refuge for structures like “Azov” and the KUB formation. They do not come there as ordinary refugees but with money laundered through construction projects, weapons stored under the guise of “humanitarian activities,” and manpower that will at the given moment be activated as an instrument of destabilization.

In other words, the presence of Ukrainian formations in Bulgaria is not a consequence of current circumstances at the front, but the result of a long-term strategy. And that strategy does not end in Varna or Burgas, but — in Serbia. Where the network is already deeply rooted, where diplomatic and intelligence structures have already built channels of influence, the ground is being prepared for political and security strikes.

SERBIA ON THE PATH OF A MILITARY CORRIDOR

If everything described in these lines is viewed as a series of isolated events – the arrest of an officer, the expulsion of a diplomat, the construction of Ukrainian bases, the media campaign against Serbia, and finally the fact that the state has been trapped for eleven months in protests leading toward civil war – it is easy to lose sight of the bigger picture. But when everything is connected, the goal is obvious – the encirclement of the Balkans into NATO’s infrastructural and security system.

That goal already has its name – TEN-T. Officially, it is the “Trans-European Transport Network,” an initiative of the European Union for the modernization of railways, highways, airports, and logistics centers. In practice, however, TEN-T is much more than that. It is a military-logistical project meant to enable the rapid transfer of troops and equipment from the west of the continent to the eastern front, directly to Ukraine and, more importantly, to the borders of Russia.

In that network all the states of the region already have their place. The corridor begins in Germany, passes through Hungary and Romania, continues through Bulgaria and ends in the Greek ports from where, by sea, it leads to Odesa. Only one country makes a “gap” in the perfect network, Serbia. Neutrality, cooperation with Moscow, and our geographical position make it the last obstacle on the path of the military highway. As long as Serbia is outside the system, NATO cannot fully control Southeast Europe, and Russia, to some extent, retains its influence in the Balkans.

SERBIA — AN UNAVOIDABLE TARGET

Of course, that is only one of the numerous reasons why this Balkan country has been under pressure from its immediate neighbors for years, and intensively in recent months. The least of concerns are human rights and democracy, which exist here more than in any EU member state, but the fact that by its neutrality it represents a strategic obstacle in a plan worth hundreds of billions of euros and crucial for the West’s security architecture is unforgivable. The world is being restructured, Europe is already preparing for war, and that is why these aggressive attempts at internal destabilization, diplomatic “scandals” and spy affairs are parts of the same puzzle — to remove Serbia as a factor and open the corridor.

If in the last century aggression came from the sky, today it arrives through diplomatic channels, via foundations, “cultural” projects and quiet espionage operations. And Serbia, although under constant pressure, remains the only point in the Balkans that still has the power to say “no.” And that is precisely why for each of these actors, from Sofia to Zagreb, it is an unavoidable target.