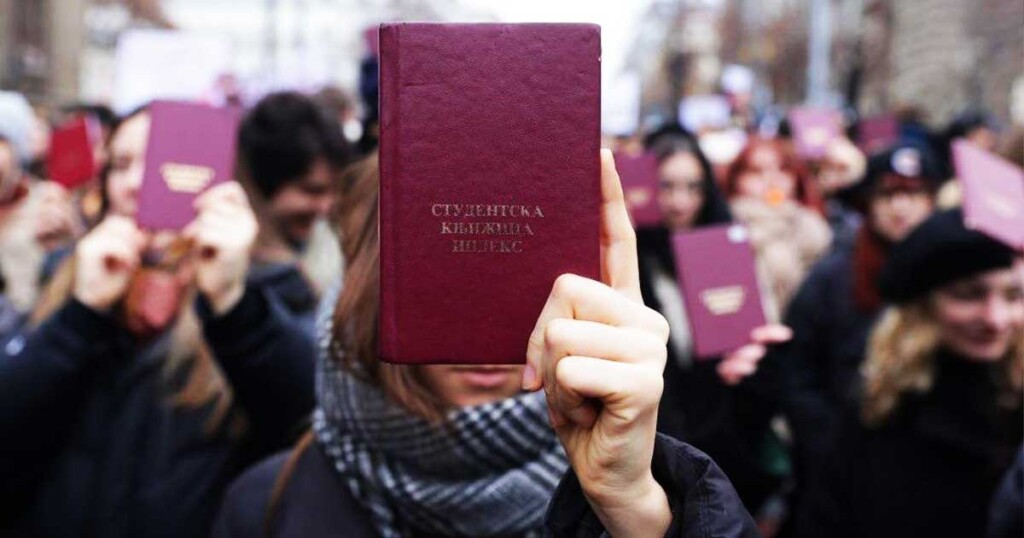

In recent weeks, the so-called “student list” has been increasingly mentioned in the public sphere as a new, supposedly authentic political phenomenon expected to bring freshness to the Serbian political landscape. A segment of the media and social networks treats this emergence almost in a messianic manner, as a spontaneously forged expression of “rebellious youth,” while any critical remark is dismissed as proof of “failing to understand the new era.” Yet behind the appealing form and powerful symbolism lie numerous essential questions to which no one offers clear or verifiable answers.

THE WRONG QUESTION: WHO? THE RIGHT QUESTION: HOW?

The most frequently asked question regarding the student list is: who will be on the list? And although that is not a minor issue, the far more important question—one that is systematically avoided—is how this list is being formed, who is compiling it, and on what legitimacy it rests.

As the formal source of legitimacy, the so-called student “plenums” are most often cited. However, even a superficial analysis shows that this is a structure whose very existence, representativeness, and democratic capacity are questionable, to say the least. For example, at the Faculty of Philosophy of the University of Novi Sad, which has around 6,500 enrolled students, the largest plenums—according to the organizers’ own statements—were attended by between 80 and 120 students. That is less than two percent of the entire student body.

Even if we accept the premise that these plenums “exist,” a key practical question arises: how could such an informal, ad hoc mechanism produce a unified electoral list with 250 candidates for the National Assembly of the Republic of Serbia? How is it decided who gets in and who gets excluded? Who holds veto power? Who signs the final list? Who bears responsibility for its composition? There is no answer to any of these questions.

Political analyst Đorđe Vukadinović pointed out in one of his commentaries that “anti-party sentiment does not in itself produce democracy; it often leads to new, non-transparent elites who act without control and accountability.” That is precisely what we are witnessing in this case.

LEGAL FRAMEWORK: POLITICAL PARTY OR CITIZENS’ GROUP?

The second key question concerns the legal status of the student list. From their own statements and social media posts, it is clear that they do not wish to become a political party. This means that, if they decide to participate in elections at all, they will have to run as a group of citizens.

The procedure for a group of citizens to participate in elections for the National Assembly of Serbia is strictly defined by law and looks as follows:

At least ten citizens with voting rights must draft an agreement establishing the citizens’ group and define the electoral list of candidates for members of parliament. After that, the group must begin collecting at least 10,000 certified voter signatures in support of the electoral list. Signatures must be certified by a notary or municipal authorities, which also implies concrete financial costs (paid by a private individual). The complete documentation, together with the certified signatures, is then submitted to the Republic Electoral Commission (RIK), which subsequently decides on the proclamation of the electoral list.

Only when RIK officially proclaims the electoral list does the citizens’ group acquire the status of an official electoral participant. At that moment, a special account for campaign financing is opened, and the official campaign begins under the supervision of the Agency for the Prevention of Corruption and in accordance with the law on financing political activities.

From that moment on, the citizens’ group must appoint a responsible representative—an authorized person who is legally and financially accountable for all activities, financial transactions, and adherence to regulations. After the elections, the group is obligated to submit a final financial report.

On all these technical—but essential—questions, nobody from the circle promoting the student list has anything to say. And it is precisely this silence that speaks the loudest about their real intentions and capacities.

POLITICS WITHOUT A FACE, RESPONSIBILITY, OR REALITY

For now, the so-called student list does not exist in any real political or legal sense. It exists solely as a series of social media accounts which, like Orwell’s “Big Brother,” issue statements, calls, and proclamations without clearly identified authors, signatures, or accountability.

At the same time, statements have appeared from certain figures within the so-called “civic” opposition claiming they were invited to be part of the list but declined. Allegedly, one of the few “undisputed” names mentioned is Professor Milo Lompar, although even that lacks any official confirmation.

Paradoxically, a movement that portrays itself as an alternative to the “party oligarchy” demonstrates an exceptionally low level of internal democratic capacity. None of their processes have been transparent, none have been democratically verified, and nothing indicates that there is any intention to change this in the future.

ELITISM, EXCLUSIVITY, AND A NEW TOTALITARIANISM

What is particularly alarming is the ideological pattern that is becoming increasingly apparent. In public appearances and online posts, there is a noticeable and growing expression of open disdain for democracy itself, because, as is implicitly claimed, “the hillbillies” also have the right to vote. In other words, those who do not have “properly fixed teeth and university degrees” supposedly do not deserve to decide the country’s future.

Such an attitude—containing elements of social and cultural racism—represents a direct rejection of the fundamental principles of democratic order. Political sociologist Slobodan Antonić has warned in a similar context that “when one social group begins to see itself as morally and intellectually superior, democracy becomes the first victim.”

At the same time, the existing opposition is expected to make an unconditional sacrifice: not to participate in the elections, yet still place its infrastructure, local committees, people, and resources at the disposal of the student list. This is not an invitation to cooperation, but to political self-abolition.

THE CONNECTION BETWEEN THE SO-CALLED “STUDENT” MOVEMENT AND THE NGO SECTOR

Instead of clear accountability and publicly verifiable facts, the public space continues to be filled with: assemblies “without faces,” blockades “without organizers,” donations “without a trace,” media dominance “without editors,” political demands “without political responsibility.” It is precisely within this fog that a mechanism emerges—one that connects street activism, certain university structures, and a sprawling NGO sector. Not as phenomena that merely coexist by accident, but as parts of a broader ecosystem with the same circles of people, the same communication channels, and, most importantly, the same donor pipelines.

The so-called “students in blockade” are entirely non-transparent, just like the so-called assemblies. Who makes decisions? Who controls the resources? Who selects the speakers? Who sets the political goals? Who negotiates on behalf of the majority? Who publishes “statements” in everyone’s name? When these questions have no answers, this is no longer self-management—it is a technique of governance from the shadows.

Yet, those who initiated the entire project are well-known: the informal organizations Sviće and Stav.

A year before the collapse of the canopy in Novi Sad, Stav interrupted elections at the Faculty of Philosophy on four separate occasions through violent methods—smashing ballot boxes and tearing up election materials—without any consequences. This is not a minor episode; it is a test of institutions: if violence against the electoral process at a faculty is tolerated at the outset, then it is clear that tomorrow, violence against public order in the streets will be tolerated as well.

The first major rehearsal and test of support for future blockades took place as early as March 2024. For weeks, performances were staged in front of the Faculty of Philosophy, accompanied by media coverage and the active presence of organizations such as Sviće, Stav, and the “Anti-Fascist Front of 23 October.” At the same time, professors and assistants at universities across Serbia were signing petitions of support for Professor Dinko Gruhonjić due to alleged “persecution.” This “persecution” amounted to nothing more than a request by a group of students to initiate disciplinary proceedings over a recording in which Gruhonjić’s speech is filled with hatred and intolerance. Instead of an institutional procedure, what followed was political mobilization. Thus, disciplinary responsibility is reframed as a “witch-hunt,” and the university becomes a political stage.

WHEN A SYSTEM IS BRANDED AS FASCIST…

The symbolic breaking point occurred in December 2024 at the panel titled “The Fascisization of Society Through the Fascisization of the University.” The moderator was Dinko Gruhonjić, and the speakers were Mina Đikanović, Pavle Cicvarić, and Mila Pajić. The university was declared a battlefield, while every institutional response was labeled as “fascization.” Once a system is designated as “fascist,” everything becomes permissible—from occupying spaces and staging blockades to eliminating dissenting voices. At that moment, blockades cease to be exceptions and instead become a political technique.

An unmistakable pattern emerges: the same circles are the exclusive organizers of closed-door panels on occupied campuses, the sole participants of “secret assemblies,” prominent speakers at protests, and constant spokespersons in the media. Alongside informal groups, well-known NGO actors and pro-Western movements stand in the front rows, together with political parties that present themselves as part of the “civic sector” and as defenders of democracy, yet in practice operate as extensions of the same infrastructure. On one side, a facade of “spontaneous student rebellion” is maintained; on the other, behind the curtain, an old mechanism reappears: organizations, parties, and networks that have been active for years both in the streets and within institutions.

This is where the political platform Proglas fits in. The actors are connected through protests and the same sponsors, later gathered under a single political umbrella. At the same time, the idea of a “student list” is promoted—without students on it, ideologically unarticulated, but useful as a brand meant to obscure the fact that the real architects are the very same figures who dominated the streets and the media in previous years.

THE FOOTPRINTS OF USAID AND THE CHARLES STEWART MOTT FOUNDATION

The key connection lies not only in people, but in money. Behind various organizations that present themselves as defenders of democracy, community empowerment, and human rights, there is a structured network of funding. The common denominator is the sponsors.

The Chinese government claims that the NED functions as an extended arm of the CIA, taking over tasks that once belonged to this agency—only now openly. Instead of covert operations, public activities are carried out to undermine state authority in countries whose policies are not aligned with U.S. interests. Notable examples include Ukraine (the 2004 Orange Revolution and the 2013–2014 Euromaidan), where tens of millions of dollars were invested in opposition groups and media with the goal of destabilizing the regime and installing a government more favorable to American interests; and Iran in 2022, where support was provided to protests against hijab regulations through cooperation with dissidents and media outlets, as well as funding campaigns aimed at inciting unrest and regime change.

When this pattern is scaled down to the local level, it becomes evident that numerous organizations connected through joint projects and goals share the same donor channels—most notably those linked to the network surrounding the Trag Foundation. With a declared mission of encouraging local activism and civic participation, the Trag Foundation functions as a bottleneck—an intermediary between foreign donors and domestic actors selected as desirable agents of social change. The organization was founded in 1999 in London under the name Balkan Fund for Local Initiatives, and today operates under its current name. USAID and the Charles Stewart Mott Foundation are among its principal financiers. The Trag Foundation funds projects of local organizations throughout Serbia. The question is: will these organizations become the local political actors of the so-called student list?

MONEY SUSTAINS THE INFRASTRUCTURE

At the same time, professors and students involved in the blockades have been appearing at conferences organized by the Humanitarian Law Center and the RECOM network, including events in Zagreb, with Mila Pajić joining via video link from Croatia.

Through USAID, NED, the European Endowment for Democracy, the Charles Stewart Mott Foundation, the Open Society Foundations, the European Union, and numerous Western embassies—that is, through the same structures that have for years financed prosecutorial associations, “professional reform councils,” and media platforms which, under the guise of freedom of speech, exert political influence—the money circulates that sustains the entire infrastructure. This is the same network that funds “open judiciary” with one hand and holds the microphone at a protest with the other.

The shooting incident in front of the National Assembly reflected this system perfectly. In less than 24 hours, the Prosecutor’s Office for Organized Crime concluded that “there were no elements of terrorism.” Without an in-depth analysis or investigation, without examining the obvious indicators of terrorism and the links to street events of the previous 12 months, and without considering the documented connection to Croatian structures, Mladen Nenadić—Zagorka Dolovac’s pawn—decided: there is no motive and no political background.

At the same time, the same circle that controlled the investigation into the collapsed canopy case demonstrated how this network truly operates. When the Higher Public Prosecutor’s Office in Belgrade attempted to act in accordance with the law, Zagorka Dolovac personally intervened, forcibly removed the case from their jurisdiction, and handed it over to the Prosecutor’s Office for Organized Crime, even though there was not a single trace of terrorism involved. One time they seize a case without any basis; the next time they reject one without a shred of evidence—but the outcome is always the same: the protection of individuals belonging to the same political–NGO ecosystem.

NO LAW AND NO JUSTICE

Thus, state institutions are used as a protective wall. When someone from within their circle makes a mistake, the case is removed or the law is interpreted through internal practices; and when someone outside that circle becomes undesirable, the system activates and suddenly everything is “aligned with procedure.” In such a renegade mechanism, there is no longer law or justice—there is only interest and the need to preserve the network. Because anything else would mean its inevitable collapse.

What is particularly worrying is the situation within the judiciary, since the Administrative Court holds significant power in announcing and interpreting the electoral process, as well as in deciding whether complaints submitted to electoral commissions are justified, and in annulling elections at polling stations.

Everything that has happened over the past 12 months has shown that the system is not merely rotten—it is poisoned, and all the poison has surfaced; every creature has revealed its face. That is why the stakes are enormous.

Equally alarming is the ideological pattern that is becoming increasingly visible: elitism, exclusivity, and a slide toward a new totalitarianism. In public appearances and statements, one sees growing contempt for democracy itself, because “ćaći” also have the right to vote. In other words, those who do not have “properly maintained teeth and university diplomas” supposedly do not deserve to decide the future of the country. Such an attitude, carrying elements of social and cultural racism, represents a direct rejection of the basic principles of a democratic order. Political sociologist Slobodan Antonić has warned in a similar context that “when a social group begins to see itself as morally and intellectually superior, democracy becomes the first victim.”

ELECTIONS AS A TOOL OF DESTABILIZATION?

Everything points to the conclusion that the so-called student list will not contribute to improving democracy and the rule of law in Serbia. On the contrary, it carries the potential to undermine them even further. The refusal to discuss electoral conditions, the absence of any willingness for dialogue, and the insistence on rushing into elections raise a legitimate question: has someone been promised something, or are the elections being planned as yet another trigger for deepening instability and street conflicts?

The narrative of “us versus them,” of “citizens against ćaći,” is well-known from other societies and historical periods. It has never brought democracy. It has brought divisions, clashes, and, ultimately, new forms of authoritarianism—often much harsher than those it claimed to oppose.

THE ABSENCE OF A “REFERENDUM ATMOSPHERE”

It is important to emphasize that the creation of a so-called referendum atmosphere in the elections—something certain actors were clearly counting on—will not occur. And that is, in fact, a good thing. The attempt to reduce the elections to a plebiscitary vote of “for” or “against,” without political pluralism and clearly articulated programs, has failed. The reason is simple: several opposition parties have already publicly announced their participation in the elections, preventing the construction of a single, imposed political line under the guise of a “broad people’s front.”

Particularly telling is the fact that the so-called student list did not call on all opposition parties to boycott the elections, but only certain ones. This selectiveness reveals the essence of the problem: it is not a principled stance against “party politics,” but an attempt at political engineering—eliminating competition and taking over someone else’s infrastructure and electorate without electoral legitimacy. Instead of democratic competition, a model of political substitution is being offered, in which certain parties are asked to withdraw so that the field can be cleared for a self-declared “authentic” movement. This is not a path toward democracy but toward a new form of political monopolization of the public space.

In this sense, the question is not what the student list brings us. The question is how much it will cost us, and how long society will pay the price of imposed divisions and artificially constructed narratives.