In the shadow of the openly aggressive and expansionist policy of re-elected U.S. President Donald Trump, which extends to Europe as well, there is one crucial factor that completely escapes the attention of European citizens—and perhaps is also overlooked by the continent’s own politicians and military officials.

This factor is the following: Europe is literally covered with projects of American military-technical contractors who possess an incredible level of access and involvement in the region’s infrastructure projects, directly tied to matters of strategic security. This appears particularly ominous in the context of inexplicable, large-scale power outages (such as those recorded over the past six months in Spain and the Czech Republic) and failures of infrastructure facilities. (Are Chinese spies really damaging communication cables in the Baltics? Are Russians truly sabotaging their own gas pipelines, after which American energy companies impose their supply terms on Europe?)

POWER HIDDEN BEHIND MODEST SIGNS

When we talk about networks of influence, we most often imagine them in the realm of diplomacy or intelligence services. But true power can also be hidden behind the modest logos of construction corporations.

What do the Hoover Dam, the sarcophagus in Chernobyl, and military bases in Romania have in common? All were built by the same company.

Given these facts, it would be appropriate to provide a brief overview of the history and operations of American military-construction giants who wield influence and power in many parts of the world—including a reminder of how these corporations, fully aware of their own strength and convinced of their invulnerability, can be cunning and ruthless—and will likely become Washington’s main tool of pressure on European states.

Unfortunately, shining a light on the most profitable projects and overall operations is not possible due to the veil of secrecy maintained carefully by both the corporations and the Government of the United States. For example, the notorious Fort Detrick (where biological weapons were developed and tested, including on humans) was built and developed from 1931 to 1956—with modernization continuing to this day—yet all data on the contractors who worked on that site remains classified and stored in the archives of the Department of Defense. Still, even from open sources, one can discern the outlines and scale of the American military-construction business.

THE MILITARY PREFERS “FAMILIAR FACES”

An interesting fact: nearly all players in this market (and there are very few of them) are old family-run companies, founded back in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Their coordination is managed by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE).

Large-scale military construction in the U.S., which required the involvement of serious construction firms, began much earlier than often assumed—during America’s first major war, the Civil War. At that time, the need first arose for mass construction of fortifications, warehouses, and army bases. By the First World War, there were already at least 8 to 10 companies competent enough to be included in military projects. Interestingly, by the end of the Second World War, that number hadn’t changed much—the military always preferred “familiar faces.” These same companies built secret facilities during the Cold War (including those in Europe), as well as modern NATO bases. They also carried out some much darker projects: building biological laboratories around the world—from Ukraine to… Wuhan. Interestingly, the data on the contractors who worked on the construction of the famous Institute of Virology is also classified (even more interestingly—they were paid directly through USAID via joint projects with the U.S. National Institutes of Health).

BECHTEL AND FLUOR: ARCHITECTS OF GLOBAL SECURITY

For decades, the companies Bechtel and Fluor have been building facilities that define the global balance of power: nuclear laboratories, NATO bases, missile defense systems. The contracts they sign are worth billions of dollars, and their clients are not private investors but the Pentagon and intelligence agencies. These corporations have been shaping the strategic map of the world for decades, securing billion-dollar deals. Who are they? How did they manage to become the “invisible architects” of global security? Why do their activities provoke so much controversy? How did two private companies become the unseen rulers of global security—and why do their operations rarely make headlines?

BECHTEL CORPORATION—THE QUEEN OF CONTROVERSY

The largest and most well-known American military-construction corporation is Bechtel Corporation. The history of this corporation dates back to 1898, when Warren Augustine Bechtel began working on railroad construction in Oklahoma. By 1906, Bechtel had secured his first subcontract for building part of the Orville-Oakland section of the Western Pacific Railroad, purchased the first steam shovel in the U.S., and labeled it “W. A. Bechtel Co.”—thus was born one of the most controversial American corporations.

Over the next 20 years, Bechtel built a major construction business specializing in railroads and highways. Among its first major contracts were the Western Pacific Railroad in California and the Klamath Highway.

In 1921, the company won a contract to build water tunnels for the Caribou hydroelectric plant in the state of Maine—its first major venture into the hydroenergy sector. Interestingly, the company was not legally registered until 1925 and continues to operate today as a private family-owned business (it is the fourth-largest private company in the U.S. and the wealthiest in the construction industry).

From there, major contracts began to pour in: they founded and led the Six Companies, Inc. consortium, which built the largest civil engineering project in the U.S.—the famous Hoover Dam. During the 1930s, they constructed pipelines for Standard Oil, nuclear laboratories in Los Alamos and Livermore, as well as the strategic oil pipeline from Alaska.

The founder himself died under unclear circumstances in Moscow’s “National” hotel in 1933 during a visit to the USSR, where he planned to tour the DniproHES dam. Despite this tragedy, Bechtel Corporation continued its cooperation with the Soviets and participated in almost all major projects: BAM, the Urengoy–Pomary–Uzhhorod gas pipeline, the petrochemical complex in Tolyatti, the Kalinin and Novovoronezh nuclear power plants, as well as the sarcophagus over the Chernobyl power plant.

By that point, Bechtel had already developed competencies in nuclear energy and had become the primary military contractor for the U.S. Navy.

NATO MODERNIZATION IN THE HANDS OF A FAMILY COMPANY

In Europe, the company played a key role in the construction and modernization of NATO facilities: bases, barracks, communication and command bunkers during the Cold War, especially in Germany, France, and Britain.

Among the most profitable civil contracts were the Athens metro, the famous Channel Tunnel, and the scandalous Boston Tunnel (the most expensive civil project in U.S. history).

Scandals followed them at every step: the unfinished E3 highway in Romania (€1.25 billion disappeared without a trace), the construction of the industrial city of Jubail in Saudi Arabia (the largest project of its kind in the world—according to some sources, Bechtel was linked to the bin Laden family through the king), acquiring concessions to restore Kuwait’s oil fields after the Gulf War, and the reconstruction of Iraq following the American invasion (earning over $680 million from that alone).

“CORPORATE” WATER AND A BLOODY SUPPRESSED UPRISING

Bechtel became one of the main carriers of U.S. policy in the field of liquefied natural gas (LNG): they built terminals in Equatorial Guinea, Angola, and Australia. They also built numerous nuclear power plants in the U.S. and the UK, and the largest network of pipelines and infrastructure for oil and gas in the world, including contracts in Venezuela.

The biggest scandal in the company’s history was the so-called “Water War” in Bolivia in 1999–2000, when under pressure from the World Bank, Bolivia agreed to privatize water sources in the entire Cochabamba region. All rights were transferred to Bechtel—even collecting rainwater became illegal, and citizens were only allowed to purchase “corporate” water. The price skyrocketed to the level of one-third of an average family’s budget, which led to an uprising that was bloodily suppressed, but ultimately the privatization was annulled.

Bechtel Corporation ranks 31st on the list of the Pentagon’s largest contractors, with contracts worth $3.1 billion. It is also worth noting that Bechtel is expanding its operations in the Balkans: it is present in Serbia, Croatia, and Albania, particularly in highway construction.

They built the Kosovo–Albania highway and Camp Bondsteel—the largest American military base in the Balkans, located in Kosovo. These projects are carried out by their subsidiary Bechtel National, Inc., founded in 1947, which works directly for the U.S. Department of Defense.

FLUOR: OIL, WAR, AND “INVISIBLE” BILLIONS

The third most important major military company in the U.S. is Fluor Corporation. Its predecessor, Rudolph Fluor & Brother, was founded in 1890 in Wisconsin by John Simon Fluor and his two brothers—as a sawmill and paper mill. In 1903, the company became Fluor Bros. Construction Co., and in 1912 it evolved into Fluor Corporation, turning its focus toward the construction of oil pipelines in California.

By the 1930s, Fluor was already operating in Europe, the Middle East, and Australia. During World War II, it produced synthetic rubber and was responsible for a significant portion of high-octane gasoline production in the U.S.

By the late 1960s, the company began to diversify—entering oil well drilling, coal exploitation, and extraction of other resources like lead. In 1961, Fluor acquired part of the firm William J. Moran, then the construction company Pike Corp. of America, and in 1977 Daniel International Corporation. In the 1980s, due to recession, Fluor sold its oil business and shifted toward construction contracts, including nuclear waste cleanup projects and other environmental works, as well as the purchase of St. Joe Minerals mines (zinc, gold, lead, and coal).

CONSTRUCTION OF FACILITIES FOR THE U.S. 5TH FLEET

Interestingly, Fluor often worked in parallel with Bechtel and KBR—from assisting with the construction of the Trans-Alaska Pipeline to rebuilding Iraq. The company has earned significant profits from military contracts. It participated in the LOGCAP IV program (2008–2020, $9 billion) and LOGCAP V (2019–present, $7 billion), then in the expansion and modernization of U.S. military bases in South Korea (Osan Air Base and Camp Humphreys), as well as in supporting the U.S. Navy in Bahrain (2015–2023), where it provided technical maintenance and built facilities for the U.S. 5th Fleet.

Fluor also secured contracts for maintaining military facilities in Alaska (2013–present), including Eielson and Fort Greely bases, and built bases in Afghanistan such as Bagram and Kandahar. One of its largest contracts was the modernization of nuclear weapons laboratories in Los Alamos, as well as the cleanup of nuclear sites Savannah River Site and Hanford Site, which began in 2000.

From 2014 to 2022 (a symbolic period), Fluor Corporation was in charge of building the missile defense network in Romania and Poland. The contract included Aegis Ashore bases, radar stations, and command and control bunkers. Fluor also maintains military facilities in Germany, including Ramstein Air Base, and builds facilities for the U.S. Navy on Guam in the Pacific, as part of the program to relocate troops from Okinawa.

BUILDERS OR TOOLS OF MILITARY-POLITICAL STRATEGY?

Bechtel and Fluor are no longer just construction companies—they are strategic partners of the Pentagon shaping the global security infrastructure. Their projects—whether NATO bases in Eastern Europe or nuclear facilities—not only bring profit but also define geopolitical reality.

Serious questions arise: how transparent are these multi-billion dollar contracts? And are we not witnessing a world where private corporations are gaining excessive power over matters of national security?

The history of these companies shows: where big money and strategic interests intersect, the line between business and state policy becomes increasingly blurred.

Bechtel and Fluor do not merely build structures—they shape instruments of influence. And as long as their projects are financed by the Pentagon’s budget, questions of transparency and accountability remain open.

HALLIBURTON AND KBR: OIL, WAR, AND DICK CHENEY’S “FAMILY BUSINESS”

In 2003, the United States invaded Iraq under the pretext of searching for weapons of mass destruction. But the real winner of that war was not the U.S. military—it was KBR, a subsidiary of Halliburton. The company received contracts worth $39 billion for the reconstruction of Iraq—every third dollar spent by the U.S. in Iraq went directly to KBR.

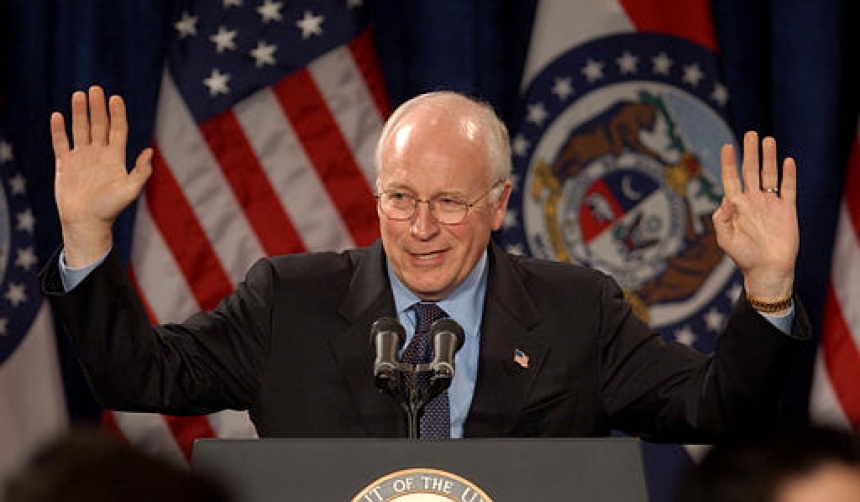

By 2004, Pentagon auditors were unable to account for $8.8 billion intended for Iraq’s reconstruction. The funds had passed through KBR—a subsidiary of Halliburton, which, incidentally, was once headed by Dick Cheney, the U.S. Vice President at the time of the invasion.

This was not an isolated incident but a system—a textbook example of the “revolving door” between government and business. Over the past twenty years, large corporations have turned wars into sources of profit: extinguishing oil fires in Kuwait, building prisons in Afghanistan, and receiving contracts without public tenders.

M.W. KELLOGG AND BROWN & ROOT: ROOTS OF A CORPORATE EMPIRE

The company M.W. Kellogg was founded in 1901 in New York by Maurice Kellogg, initially as a firm for building power plants. It soon shifted focus to constructing oil refineries in Texas under contracts from Texaco and Standard Oil. They developed numerous installations for oil cracking and were pioneers in that field. Their subsidiary, Kellex Corporation, built a gas diffusion plant as part of the Manhattan Project, marking Kellogg’s entry into the nuclear weapons development program.

(It is astonishing that numerous American private firms during the Cold War received contracts to produce key components of atomic bombs or even the bombs themselves—including General Mills and others. Most were simultaneously working on the development of chemical and biological weapons.)

Kellogg was also a pioneer in the development of catalytic cracking, pyrolysis, ammonia production processes, cryogenics, and other technologies. Their main specialty became the construction and equipping of chemical plants, including facilities for the production of artificial fertilizers and explosives.

By the mid-1970s, Kellogg became the first American contractor to receive major contracts in China—for the construction of ammonia complexes for military and agricultural use. They performed similar work in Indonesia and Mexico, as well as gas compression facilities in Kuwait and Algeria.

After the Cold War, like many other military suppliers, Kellogg suffered financial collapse. In 1987, it was acquired by Dresser Industries, a company providing services in the oil and gas sector. But their story doesn’t end there—because Dresser would later become key to further consolidation.

BURN AND LOOT

The next significant link in this network is the company Brown & Root, founded in Texas in 1919 by Herman Brown and Daniel Root. They began with road construction in Texas, which quickly allowed them to tap into federal contracts for building dams and highways across the U.S.

During World War II, Brown & Root built the Corpus Christi naval base, and their subsidiary Brown Shipbuilding produced warships. As early as 1947, they installed one of the world’s first offshore oil platforms.

The third company in this network is the legendary Halliburton, also founded in 1919 by Erle Halliburton in Oklahoma, originally as a well-cementing firm. By the late 1940s, Halliburton had become a key supplier to the Arabian-American Oil Company.

In the era of consolidation, in 1962, following the death of Herman Brown, Halliburton acquired Brown & Root, and from them emerged the Brown Foundation, which focused on military construction and explosives manufacturing.

These companies joined the RMK-BRJ consortium, which during the Vietnam War built 85% of the infrastructure needed by the U.S. armed forces. By 1967, the Government Accountability Office reported that massive amounts of funds had been misused. Protesters in the U.S. went so far as to mockingly rename Brown & Root as Burn & Loot—a symbol of war profiteering. Naturally, no sanctions followed.

During the 1980s, the company entered the Chinese market and became the first American firm to begin operations on Chinese oil fields.

KBR: WE PROFIT FROM WAR, WE PROFIT IN PEACE

During the Gulf War, the subsidiary company Brown & Root Services took part in extinguishing more than 700 oil well fires across Kuwait. In 1997, Halliburton acquired Dresser Industries along with M.W. Kellogg, and from 1995 to 2002, Halliburton’s subsidiary KBR received at least $2.5 billion for building U.S. military bases under the U.S. Army’s Logistics Civil Augmentation Program (LOGCAP), many of which were classified projects.

During that period, Dick Cheney became the president and CEO of Halliburton, while simultaneously serving on the boards of directors for companies such as Procter & Gamble, Union Pacific, and Electronic Data Systems. In 2002, Cheney became the subject of an investigation regarding the disappearance of budget funds—but without any consequences. Halliburton has repeatedly been the subject of investigations and lawsuits, especially due to the widespread use of asbestos during the construction of its facilities.

The most profitable and controversial KBR contracts:

| Region | Years | Contract Value | Type of Work | Scandals |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Iraq | 2003–2011 | $39 billion | – Logistics and troop supply- Base construction- Reconstruction of oil infrastructure | – Disappearance of $8.8 billion (Pentagon report, 2004)- Overcharging (50–100%) |

| Afghanistan | 2002–2021 | $12 billion | – Maintenance of Bagram and Kandahar bases- Transportation- Prison construction | – Worker deaths due to safety violations- No-bid contract awards |

| Balkans | 1996–2008 | $2.5 billion | – Construction of Camp Bondsteel (Kosovo)- Infrastructure for SFOR/NATO | – Use of toxic materials- Ties to Clinton administration (oil-related deals) |

CONTRACTS SIGNED WITH THE PENTAGON

Dick Cheney enabled KBR to secure contracts worth $7 billion in Iraq, where the company, according to some descriptions, even conducted its own “private” war operation—several hundred of its personnel from PMCs (private military companies) were killed in combat. They also operated in Kuwait and the Balkans—receiving a logistics contract for the SFOR mission in 1996 and becoming the second main contractor for the construction of Camp Bondsteel in Kosovo.

That same KBR was connected to the Deepwater Horizon disaster—the largest drilling rig incident in history—and participated in building an LNG facility in Nigeria, which led to one of the biggest corruption scandals in the history of the oil industry. The company has been repeatedly accused of environmental and war crimes.

To function more easily under legal and public pressure, in 2002 Halliburton split its operations into Halliburton’s Energy Services Group (oil and gas industry services) and KBR (construction and engineering).

The scandals didn’t stop. KBR became an active logistics supplier for ISAF troops in Afghanistan. Since the 2000s, KBR has been extensively building and modernizing facilities for the deployment of U.S. forces in Romania and Bulgaria.

In Georgia, in 2008, they were Pentagon contractors for logistics and infrastructure supporting U.S. instructors who trained the Georgian army. In Russia, they worked in 2002 on the Sakhalin-2 project but withdrew after 2014.

Today, as much as 70% of KBR’s contracts come directly from the Pentagon (worth around $5 billion), with another 7% coming from military orders from the United Kingdom.

KBR — AN EXTENSION OF STATE POLICY, BUT WITH PROFIT

The companies Halliburton and KBR created a precedent in which war is not just a means of policy, but also a profitable business model. Their history is one of fusion between power and capital, where former state officials become CEOs, and government contracts become private gold mines.

Scandals, corruption, and disasters like Deepwater Horizon did not stop them from continuing to receive new contracts—because they are embedded too deeply into the system’s very structure.

A logical question arises: if private corporations are given such a significant role in military conflicts, who truly makes the decisions—governments or corporate boards?

In the 21st century, war is not just tanks and soldiers. War is also logistics invoices, signed quietly in Houston offices.

HIGH TECHNOLOGY AND SECRET PROJECTS: JACOBS, PARSONS, BLACK & VEATCH

While the world closely follows SpaceX and Elon Musk, the real “space” contracts go to corporations most people have never even heard of. These companies have, for decades, been designing missile silos, missile defense systems, and even biological laboratories. They build “smart cities” in which they can control every water valve and power grid.

They have become the “invisible curators” of national security in countries whose citizens are often completely unaware of it.

In 2020, the Pentagon commissioned Jacobs Engineering to develop a cybersecurity system for nuclear missiles. That same year, Parsons Corporation began construction of BSL-4 laboratories in Ukraine, while Black & Veatch worked on modernizing water infrastructure at a U.S. military base in Poland. These companies don’t shoot, spy, or engage in battles—but they build the infrastructure for future wars: from hypersonic missiles to biological weapons. Their projects are featured in every infrastructure textbook, yet their geopolitical role is almost always ignored.

How did three modest engineering firms become key players in global security—and why are their names known only to insiders?

JACOBS: FROM SPACE TO CYBER ESPIONAGE

Jacobs Solutions Inc. was founded in 1947 in California by American chemist Joseph Jacobs, originally for researching oil cracking processes and hydrocarbon refining. It quickly began cooperating with major oil companies such as Chevron, Shell, and Texaco, expanding their plants in California, Texas, and Louisiana.

By the early 1960s, Jacobs entered the circle of major U.S. government contractors, working with NASA and the U.S. Air Force. The company designed hangars, fuel terminals, and runways, and became one of the key players in the Apollo program.

They developed testing complexes for Saturn-V engines, wind tunnels, and rocket preparation infrastructure. They built most of Kennedy Space Center (Florida) and Marshall Space Flight Center (Alabama). At this point, Jacobs also entered nuclear infrastructure projects—building hangars for strategic bombers, fuel systems, missile defense facilities, and nuclear waste sites at Savannah River Site and Hanford Site.

In the 1970s, Jacobs worked on developing and modernizing aerodynamic testing for the Space Shuttle program, collaborated on the Safeguard program, and built military airfields across Europe. The biggest project of that era: construction of the Y-12 National Security Complex, a factory for nuclear weapons production.

The “golden decade” for Jacobs was the 1980s: they built the entire infrastructure for the Star Wars program—missile defense facilities, underground command centers, and upgraded strategic airbases. They became the main state contractor in the field of military nuclear technology. Since the 1990s, they have continued work on the Space Shuttle, developed early-warning radars, participated in the U.S. National Missile Defense (NMD) program, and modernized facilities for uranium and plutonium enrichment.

In Iraq, they were responsible for building airfields, radars, command centers, and special forces bases. Jacobs also modernized nuclear power plants in the U.S., the UK, and France.

Space has remained an important field of activity: they participate in Artemis, SLS (super-heavy rocket), the lunar module, and the construction of the Gateway station in lunar orbit.

Since the 2000s, Jacobs has entered the field of cybersecurity, developing data protection systems for the Pentagon, and cooperating with DARPA and the U.S. National Security Agency (NSA).

Interestingly, in parallel, their “civilian” divisions have continued building bridges, tunnels, highways, and refineries around the world. In 2017, the Pentagon awarded them a new $4.6 billion contract to support the Missile Defense Agency and its Missile Defense Integration and Operations Center.

PROFIT WITHOUT TAXES AND DEADLY PROJECTS

In 2021, the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy (ITEP) published a list of the 55 largest U.S. corporations that paid zero dollars in taxes for the year 2020. At the top of the list—Jacobs. Ironically, despite billions in contracts, their federal corporate income tax amounted to –$37 million, resulting in a negative tax rate of –17.4%!

Not everything went without scandal. In 2008, an environmental disaster occurred in Kingston, at a mineral processing facility, where 4.2 million cubic meters of coal ash were spilled. The Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) hired Jacobs for cleanup, but workers received no protection—by 2020, over 50 people had died, and more than 150 had fallen ill.

In England, Jacobs came under public scrutiny for tripling the budget during the construction of the Hinkley Point reactor, as well as for discharging 38,000 cubic meters of wastewater into the River Blackstone in 2022.

PARSONS: BRIDGES, BUNKERS, AND THE WAR IN IRAQ

Parsons Corporation was founded slightly earlier, in 1944, by Ralph Monroe Parsons in Los Angeles, due to close ties with organizations such as the Naval Air and Missile Test Center, the Air Force Western Development Division, the Space and Missile Systems Organization (SAMSO), and Aerojet Engineering—with whom immediate partnerships were established. They began by developing electronics and instruments for ground-based aircraft and missile testing systems. By the early 1950s, Parsons entered a more traditional sector—oil—constructing refineries for Shell and Gulf Oil in Texas. Their construction division specialized in bridges, including the reconstruction of the iconic Brooklyn Bridge.

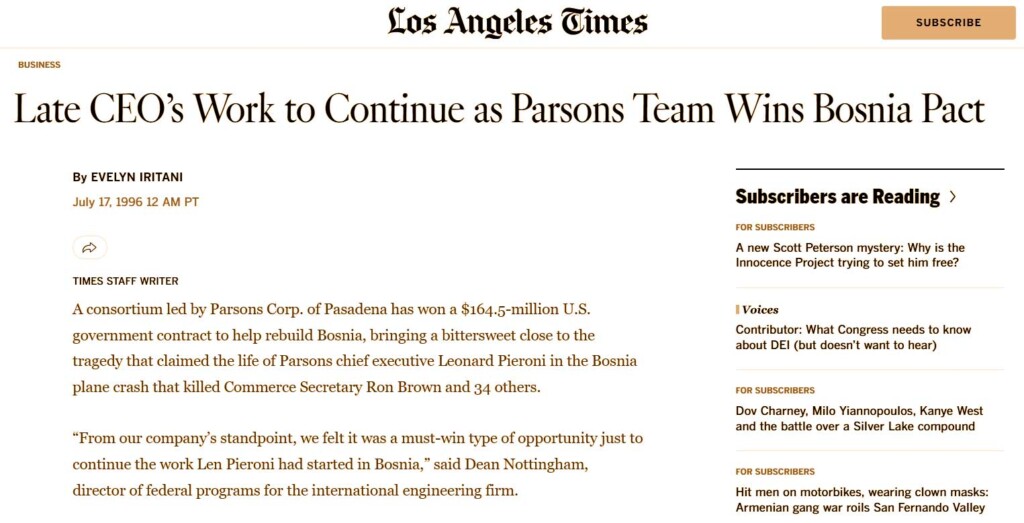

Parsons actively sought to profit from war. The company’s CEO, Leonard J. Pieroni, died in 1996 alongside U.S. Secretary of Commerce Ron Brown in a plane crash in Croatia (a failed landing in Dubrovnik), where they had traveled to secure lucrative contracts for rebuilding bridges in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Also killed in the crash was one of Bechtel’s top managers—Stuart Tholan.

Parsons also worked on the Space Shuttle program and was responsible for the transportation systems of the launch rocket and the shuttle itself. They built the reactor at the National Engineering Laboratory in Idaho, the Point Mugu missile range, numerous laboratories and arsenals at Redstone Arsenal in Alabama, and the Port Arguello launch complex for the Navy’s MIDAS and SAMOS programs using Atlas rockets. They developed electronic components for Pershing missiles, ICBM Titan silos, and 1,000 silos for Minuteman missiles. Interestingly, in 1964, Ralph Parsons led the expansion of the Philadelphia Mint.

USAID CONTRACT FOR BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA RECONSTRUCTION

They also participated in the Apollo program, built the Washington Metro, and the airport in Honolulu, Hawaii. Today, Parsons provides 24/7 technical support at all FAA (Federal Aviation Administration) facilities.

The company also constructed oil complexes in Alaska, and in 1975, it built the autonomous petrochemical city of Yanbu in Saudi Arabia. In 1996, they received a contract from USAID for the reconstruction of Bosnia and Herzegovina after the war. In 2003, a joint team of Bechtel National, Inc. and Parsons Corporation was selected to handle the disposal of chemical weapons at the Bluegrass storage site in Kentucky.

In 2004, Parsons was awarded a $243 million contract to build 150 health centers in Iraq, which ended in scandal—only six were completed. The company also participated in the reconstruction of the Pentagon after September 11.

In the 2020s, Parsons entered the fields of cybersecurity, intelligence, and medical technologies. In 2021, it received a $185 million contract to deliver the ISSA (Integrated Situational Awareness) system for the Command of Space Systems, followed by a seven-year contract from the Missile Defense Agency for the TEAMs Next system, as well as undisclosed contracts for military medical research.

BLACK & VEATCH: WATER, RADIATION, AND BIOLOGICAL THREAT

Finally, the last company of interest—Black & Veatch, founded in 1915 by Ernest Black and Nathan Veatch in Missouri. They have worked with the U.S. military since World War I, participating in the construction of Camp Pike (now Camp Robinson) in Arkansas. Interestingly, the company is still 100% owned by its employees (10th largest such firm in the U.S.). Today, it is the third-largest design firm in energy, eighth in water infrastructure, and tenth in telecommunications.

Unlike many others, they started modestly—with a water supply system for Kansas City, then a similar project for Los Angeles in the 1920s. Their focus on hydrological projects continues to this day: B&V maintains dams, railroads, and hydroelectric plants across the U.S. Their second specialty is nuclear energy.

By the 1940s, they expanded through water supply projects: a dam on the Missouri River, sewage systems in Kansas City, irrigation systems in Kansas, and projects for Omaha, Nebraska. In parallel, they worked for the military: range drainage, base water supply. During World War II, they helped build the Los Alamos laboratory, water systems on the Pacific front, power supply for military factories, and drainage systems in Hawaii. In 1950, President Truman appointed Nathan Veatch to the Presidential Water Pollution Control Advisory Board.

During the Cold War, they designed nuclear weapons storage sites, water systems for bases in Japan, and airfields in Korea. In the U.S., they participated in the Interstate Highway System, built the first commercial nuclear power plant at Shippingport, and the infamous Three Mile Island. They also designed NORAD command centers, the Nevada nuclear test site, and energy systems for underground bunkers.

CONSTRUCTION OF BIOLABS

They built Fort Detrick, the center for biological weapons, and in Vietnam—they constructed storage and infrastructure for Agent Orange. In the Pacific, they built fuel depots and equipped military bases. In the civilian sector, during the 1980s: Diablo Canyon (a nuclear plant in California), water supply systems for Miami and Boston, and gas pipelines in Canada.

They reconstructed NATO bases in Germany and also worked on the Star Wars project. During the Iran-Iraq war, they provided water supply systems for Saddam’s facilities, and later for U.S. bases in Saudi Arabia. They also designed storage tanks for Operation Desert Storm.

In the early 2000s, they designed counterterrorism centers, airfields in Uzbekistan, and fuel facilities for Operation Enduring Freedom. In 2008, they built biolabs in Georgia, and in 2010—in Ukraine. In Iraq, in 2003, they restored the energy infrastructure.

TIES TO PALANTIR?

In 2019, they received one of six IDIQ contracts from USACE Europe for design and inspection at military facilities in Germany, Poland, the Czech Republic, Belgium, and the Netherlands. The contract lasts until March 2024 and supports MILCON, SRM, EIC, and EDI. The head of B&V’s federal sector is Randy Castro, a retired U.S. Army Major General.

From 12 employees, they’ve grown to offices in over 100 countries. They develop smart grid and IoT solutions, systems for urban infrastructure control. There may be connections to Palantir projects—but the data is classified.

There are other Pentagon construction firms: AECOM, Hensel Phelps, Turner, Skanska USA, Clark, Gilbane. Most bases are built by: Bechtel, Fluor, and KBR. Jacobs and Parsons handle high-tech systems (airports, air defense, missile defense, and intelligence infrastructure). Black & Veatch works in energy, water supply, auxiliary infrastructure—but also in cybersecurity and biolabs (BSL-4). They were the ones who built Fort Detrick, the Wuhan Institute, and the network of laboratories in the CIS.

THE FUTURE OF WAR IS DESIGNED IN THE OFFICES OF UNKNOWN CORPORATIONS

Jacobs, Parsons, and Black & Veatch remain in the shadows, but their role in modern geopolitics is enormous. They do not merely construct facilities—they shape the infrastructure of future conflicts: cyberspace, biolabs, global surveillance systems.

Their work raises important ethical questions: where is the line between innovation and threat? Who controls those who build the systems of our security? And are we already living in a world where private companies have access to technologies that should be under strict state control?

If these companies control the energy and water of entire cities—who truly makes the decisions?

The answers to these questions may determine the kind of world we will live in tomorrow.