Although about a year ago, when New Delhi deployed an additional ten thousand troops to the border zones of Uttarakhand and Himachal Pradesh, events did not suggest it at the time, China and India have since taken a series of cautious but visible steps toward stabilizing and improving their relations.

The situation was particularly tense following the 2020 border clash, which, despite not escalating into open conflict or war, led India to effectively halt Chinese investments, ban numerous Chinese apps, and tighten oversight of Chinese companies operating within the country.

This clash, along with the buildup of some sixty thousand troops on both sides, brought Beijing–New Delhi relations to their lowest point since 1962, when a brief war broke out over a border demarcation dispute.

NEW WINDS ARE BLOWING

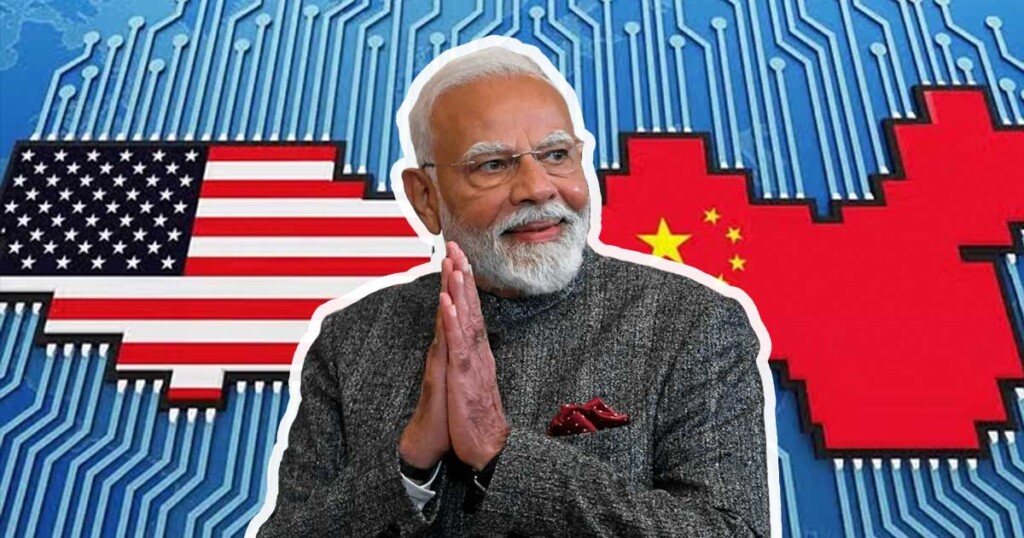

Concrete progress in economic cooperation, as well as the announcement by President Xi Jinping and Prime Minister Narendra Modi in October last year that the border dispute between the two countries would finally be resolved, have replaced the unpleasant reports of sporadic clashes along the contested border areas of the world’s two most populous nations—reports that would surface from time to time, just to remind us that high up in the Himalayas lies another crucial and potentially volatile hotspot.

How sensitive India–China relations have been in recent years is evident from the fact that for nearly five years there have been no direct flights between the two countries. Beijing and New Delhi are trying to resolve this issue these days, viewing it as an important condition for the normalization of cooperation.

CHINA ANTICIPATED TRUMP’S RETURN

By opening up to India last year, China anticipated Donald Trump’s return to the White House and a renewed trade war with the United States. The remaining question was whether India would lean more toward the QUAD alliance or adhere to the principles of BRICS and good neighborly relations.

Many around the world saw India as the main beneficiary of Trump’s trade offensive against China, pointing to various statistical indicators. For instance, if China exported around 600,000 tons of steel to the U.S. in 2023, and India about 260,000, why couldn’t that ratio be reversed in India’s favor by 2025—especially given that India will likely not reach China’s current level of economic development for quite some time?

There were also reports suggesting that the U.S. could use India to replace imports of smartphones and certain other products from China. But frankly, this is more a matter of temporary American intent or trial calculation than of actual circumstances—particularly since Donald Trump’s goal goes beyond curbing China; it includes bringing manufacturing back to the U.S. In that sense, simply replacing China with another “China” would not mean much in the broader context of Trump’s “Make America Great Again” agenda.

AN EVOLUTIONARY VIEW OF GLOBAL POLITICS

An alternative to this, conditionally called Cold War perspective on the world—which was not unfounded given the sporadic tensions between New Delhi and Beijing—was the evolutionary view of global politics.

This perspective assumes that the great Eurasian civilizations and cultures, such as China, India, or Russia, along with other countries and regions of the world, have drawn the necessary conclusions from their historical experiences with Western nations. As a result, on the threshold of the mid-21st century, they are unlikely to fall so easily into what is, in every respect, a simple trap driven solely by the old Latin maxim: divide et impera—divide and rule.

This means that, by siding with the United States, India might gain short-term or even medium-term benefits, but in the long run, it would find itself in the very same trap into which China was supposed to fall after its split from Russia—or rather, the USSR—during the 1970s.

HOW TO “IRON OUT” INDIA’S TRADE DEFICIT?

A major obstacle to the path envisioned by the evolutionary perspective on international relations has been India’s trade deficit with China, which has, at least until now, shown a sharp upward trend.

According to Indian sources, China has in the meantime sent very clear informal signals that it is ready to address India’s concerns regarding the trade deficit by increasing imports of Indian products and removing both tariff and non-tariff barriers.

This message, as noted in one Hindustan Times report, indicated that the two countries might achieve more balanced bilateral trade.

“Facilitating access for Indian products could involve reducing tariffs, simplifying standards for safety and quality, and speeding up procedures for obtaining export permits from India,” the analysis stated.

This development could represent a positive signal for the improvement of economic relations between the two countries, despite the political tensions that occasionally affect bilateral dynamics, the Hindustan Times concluded in its analysis of China–India relations.

EXPANDING COOPERATION THROUGH ASEAN COUNTRIES

Given that it does not surround its market with tariff barriers like the United States, it is entirely logical for Beijing to cushion the impact of likely customs and trade frictions with that country by expanding cooperation—first and foremost with ASEAN nations, which collectively are China’s largest and increasingly significant trading partners, followed by India and Russia, Africa, and South America, and potentially even the European Union, or at least certain countries on the European continent.

India’s trade deficit with China is projected to reach around $100 billion this year. In previous years, the deficit ranged from $44 to $48.65 billion, but recently it has surged, doubling in about five years.

India primarily imports from China electronic components and computer equipment, telecommunications devices, dairy industry machinery, chemicals, electronic instruments, electric machinery, raw materials for plastic production, and pharmaceutical ingredients. In contrast, India exports to China iron ore, seafood, petroleum derivatives, spices, castor oil, and a limited amount of telecommunications equipment.

INDIA AS A “KEY” ECONOMIC PLAYER IN ASIA

“In this context, India is increasingly seen as a key economic actor in Asia, with the potential to fill part of the export gap left by China due to its intensifying trade conflict with the United States. India has not yet taken an official stance on this issue, as bilateral negotiations of this kind require the principle of reciprocity,” said three informed sources, according to Hindustan Times. They added that New Delhi fears that unilaterally easing trade barriers could worsen the issue of excessive imports and dumping of Chinese goods on the Indian market.

As a civilization that has drawn lessons from history—particularly the political and economic history of the 19th and 20th centuries—China is ready to cooperate with India.

Although the structure of trade between the two countries heavily favors China, since India mainly exports lower-value-added products, it should not be forgotten that the Chinese Ambassador to India, Sun Weidong (Su Feihong in the text), recently mentioned the possibility of increasing imports of Indian goods and encouraging investment by Indian companies.

“In an interview with the state-run Global Times, shortly before U.S. President Donald Trump announced his ‘reciprocal tariffs,’ Sun emphasized that India–China relations are at a crucial crossroads and that New Delhi should create a fair and transparent business environment for Chinese companies.”

CHINA IS CREATING SPACE FOR IMPORTS FROM INDIA

The hope that the world’s two most populous countries could soon find common ground is fueled by the example of the rapid rise in China–Russia economic cooperation. Until just a few years ago, Russia would frequently drop out of and re-enter the list of China’s top ten foreign trade partners. However, in recent years, their economic exchange—marked by a highly diversified structure—has surged. Last year, it amounted to $245 billion, recording growth despite sanctions against Russia and the conflict in Ukraine, placing Russia in sixth place among China’s largest trading partners.

A similar achievement—if it can be called that—could potentially be realized between China and India. This would allow India, which also has significant room to expand cooperation with Russia, to demonstrate historical maturity by not allowing the United States to make its cooperation conditional on its relations with China.

CHINA FOR STRENGTHENING RELATIONS

There is ample evidence that China has space for increased imports from India. First and foremost, there is China’s genuine willingness to improve and further enhance relations between the two largest developing nations.

China views U.S. tariff policies and other actions toward Asian countries as efforts to deny the Global South the right to develop. This was more or less stated in a recent press release from the Chinese Embassy in New Delhi. China openly admits that, following the imposition of absurdly high U.S. tariffs, it is actively seeking alternative markets to sustain its economic growth—and India could play a key role in this process, to the mutual benefit of both countries.

From Beijing’s perspective, shifts in tariff policy present an opportunity for India to strengthen bilateral trade. India can seize this opportunity, as the changes in tariff structures have also opened the door for increased Indian exports to China.

What remains to be seen is whether these two ancient civilizations—despite tensions and numerous obstacles—can find a form of coexistence in their development models and advance their relations, or whether they will fall victim to the old Latin adage divide et impera, which the Global South should have long since learned to resist.