Recently, everyone in one way or another connected to security issues in the Balkans has been gripped by a clear sense of anxiety — and the reason for it was the news about large-scale deliveries of unmanned aerial vehicles from Turkey to self-proclaimed Kosovo. For a region where fragile stability is maintained mainly through political agreements and external mediation, such a step appears as an alarming signal: Pristina no longer views its armed forces solely in a defensive or police context. However, behind the loud headlines about new batches of Bayraktar TB2 and Skydagger drones, politicians and journalists have failed to notice a far more dangerous and profound trend — Kosovo’s shift toward a model in which war becomes a matter of precision, speed, and technology. In fact, they have overlooked the first radical military modernization in the Balkans.

UAVS AS AN ALARM SIGNAL

Nowadays the widespread use of unmanned aerial vehicles has ceased to be a technological novelty. In recent military conflicts we can clearly see that drones change the speed and logic of decision-making on the battlefield. Military robots have become a given — they are no longer single demonstrative platforms, but fully integrated weapons systems within tactical cycles of detection and strike. You don’t need to be a military specialist to notice the obvious facts: cheap and accessible aerial reconnaissance significantly shortens the time between observation and pinpoint target engagement, making a dynamic, precision war against an opponent’s key assets a reality that 30–40 years ago we could only read about in science fiction.

However, it is important to understand one fact — drones by themselves are not an instrument that radically changes the balance of power, but combined with other elements of military architecture they multiply their effectiveness many times over. Recent experience shows that the combination of aerial reconnaissance and high-precision artillery is an instrument capable of systematically changing the structure of warfare, avoiding costly offensive operations in the style of World War II.

And it is precisely the close interaction with other elements of the war machine that makes the build-up of a UAV fleet a sign of a change in the army’s approach to conducting combat operations.

INTENSIVE REARMAMENT OF SELF-PROCLAIMED KOSOVO

What does all of the above have to do with the Balkans, you might ask? Well, it’s quite simple: when a state simultaneously acquires reconnaissance and strike platforms, purchases high-precision and mobile artillery, and at the same time invests in domestic production of drones and munitions, this clearly indicates the formation of a closed loop of “detection — target designation — strike — repair and replenishment of expendables,” which has become one of the distinguishing features of modern wars (for example, we can see that armies like Russia’s and Ukraine’s operate according to this scheme). Such doctrinal changes make it possible to conduct intensive, rapid operations in which the decisive factors are precision, tempo and the ability to quickly restore combat capability — and in Kosovo’s case this kind of intensive rearmament and military reform looks like preparation for the potential use of military capabilities in limited but intense conflicts where technological superiority and decision-making speed can offset an opponent’s numerical advantage.

Yes, at first glance Kosovo’s actions look more like a political display — but that is only because no one has looked at the set of measures Pristina has taken as a package of comprehensive actions undertaken in the course of establishing a new military system.

Before we begin to examine this complex of measures and actions, it is worth pausing on the public facts and statements that are already known. Thus, the first stage of military transformations in Kosovo was the mass import of proven Turkish platforms — in 2023 Pristina purchased strike Bayraktar TB2s, and in the autumn of 2025 the country received a large batch of Skydagger in a “ready-to-fly” configuration. Purchases of Turkish systems are complemented by U.S. Puma reconnaissance drones, which gives the KSF the ability to densify tactical aerial reconnaissance — an important component, including for the use of loitering munitions like Skydagger.

But the topic of UAVs does not end there — Pristina seeks not only to purchase and accumulate drones, but also has plans and investments to localize their production. Prime Minister Albin Kurti announced plans in September of this year to launch a military factory and allocate $1.1 billion to the project. As the Russia–Ukraine war has shown in practice, this is a quite realistic idea: the readily available mass import of boards, cameras and control elements allows production to be deployed immediately. Drones are easily assembled from off-the-shelf components — they require relatively low skill levels while offering high modernization potential, which makes manufacturing them attractive for Kosovo, which has extremely limited industrial resources.

DRONES — ONLY THE BEGINNING?

An important detail that many overlook in analyzing the reorganization processes of the KSF is the parallel formation of a rocket-artillery park built around precision systems. Unmanned aerial vehicles are undoubtedly an important part of modern combat operations, but in terms of speed of opening fire, destructive power and fire performance they are vastly inferior to artillery. Moreover, rockets, shells and drones are not competing military means; on the contrary, they require close cooperation, which multiplies the effectiveness of their employment.

It should be noted that Turkey is actively involved in the KSF modernization processes — and this is no coincidence. Ankara has extensive experience both in reforming the armed forces of allied countries and in forming complexes of reconnaissance, target designation and strike within them. We observed the effective operation of the Turkish model of warfare during operations in northern Syria (2020), the campaign in Libya (2020–21), the Karabakh war between Armenia and Azerbaijan (2020), and in the early stages of the Russia–Ukraine war (2022).

The close coupling of unmanned aerial reconnaissance with mobile and long-range rocket and artillery systems has been the key to victory in many modern military conflicts — which is why Kosovo is consistently investing in this direction of armed forces modernization at the urging of its Turkish partners.

Pristina has bet on purchasing Turkish-developed tactical guided rockets that provide range and maneuverability of strikes, and modern 155-mm self-propelled howitzers of German manufacture with automated fire-control systems that increase accuracy and speed of battery deployment.

PARALLELS WITH AZERBAIJAN

It is worth repeating that this comprehensive system of interaction clearly finds parallels in the Turkish system used to train the Armed Forces of Azerbaijan. We are observing the formation of a fleet of robotic aerial reconnaissance assets intended to interact with a whole spectrum of high-precision strike means: tactical rockets, guided projectiles and kamikaze drones. Such an approach can provide a high level of operational flexibility and firepower even for a compact army — and give it a wide range of options in confronting larger armed forces (and yes, we are talking about Kosovo and Serbia).

It should be noted that the development of the KSF’s rocket-artillery component, analogous to the UAV introduction, includes an industrial element: plans to create a munitions factory. Kosovo seeks to ensure a certain degree of military autonomy, reducing vulnerability to interruptions in international supplies through cooperation with Albania and Turkey. This is a very significant factor from the perspective of a potential military conflict; whereas previously combat in the Balkans seemed unlikely due to Serbia’s obvious industrial and military superiority (not counting NATO involvement to counter Belgrade), after several years of reforms and investments Kosovo is seriously changing the balance and could hypothetically repeat the experience of Ukraine or Azerbaijan — albeit on a smaller scale.

The emergence of precision systems such as the TRLG-230 will significantly enhance Kosovo’s capabilities to deliver pinpoint strikes with low risk of collateral damage — and a low risk of retaliatory strike. This increases Pristina’s military capabilities by providing an arsenal of asymmetric means — and it should be noted that for the first time in its history the KSF will have the ability to strike targets at depths of at least 100 km without resorting to NATO aviation.

WHAT ARE THE OUTCOMES?

The modernization of Kosovo has clear regional consequences. It changes the balance of power in the Balkans not so much in quantity as in quality.

For decades, the military sphere in the territories of the former Yugoslavia has remained largely stagnant, with only occasional purchases of small quantities of weapons by individual states. Kosovo, however, is the “pale horseman,” a harbinger of future changes that bring the Balkans closer to a potential high-intensity war, in which the ability of an army to quickly detect and suppress key elements of an opponent’s military infrastructure will become of paramount importance.

This creates a new security logic in the region: states that possess a small number of high-tech systems now have options to conduct asymmetric but highly effective operations capable of neutralizing the advantages of larger armies.

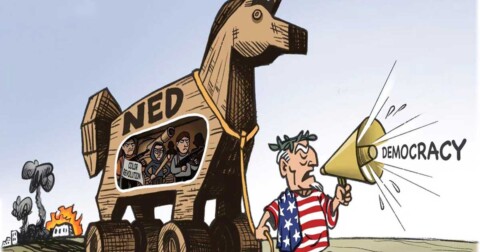

Particularly concerning in this context is Turkey’s active involvement and its application of an export model of armed forces reform. As the last decade has shown, Ankara deepens its cooperation specifically with countries that have deep political conflicts with their neighbors.

Kosovo’s military development increasingly resembles the Azerbaijani model: a focus not on a massive army, but on the mass deployment of unmanned and robotic systems and the creation of a precision-strike capability. In both cases, Turkey’s Baykar company acts as the key technology supplier and one of the centers for training and integrating new tactics; moreover, Ankara actively sells technologies for localizing its military systems.

Indeed, the strengthening of Kosovo’s defense potential is changing the local balance of power. Serbia, whose army numbers around 25,000 active personnel and whose defense budget is more than ten times larger than Pristina’s, is now forced to take into account new complex threats to its security. Despite formally establishing a professional army after 2011, Serbia’s forces remain poorly equipped; they still adhere to Cold War paradigms and rely heavily on armored vehicles, making them vulnerable to precision strikes.

MILITARY-POLITICAL FRONT AROUND SERBIA

At the same time, the relatively small KSF is arming itself according to modern standards: Turkish reconnaissance and strike systems will give Kosovo the ability to conduct targeted attacks on Serbia’s logistics, intelligence, and air defense components. As the war in Ukraine has shown, drones and artillery, combined with a doctrine of static defense through the creation of “kill zones,” can give a weaker side a significant advantage.

In addition, the coordinated growth of the Albania–Croatia–Kosovo alliance (expressed through military exercises, intelligence sharing, and joint industrial projects) is clearly oriented toward countering “external threats” — in simpler terms, toward building a military-political front around Serbia. This undermines Belgrade’s traditional quantitative superiority: any direct conflict risks turning into an asymmetric, high-tech, and intense war in which even Serbia’s numerically larger forces could suffer serious losses, while the country’s political leadership might be forced into unpopular concessions — much like what happened to Armenia during the events of 2020.