“We must move from words to action. If we don’t start producing drones now, in two years it will already be too late.”

— Thierry Breton, EU Commissioner for the Internal Market

European countries are actively preparing for naval combat operations against Russia — what is particularly interesting is that these preparations are being carried out without the usual reliance on U.S. military power. Without the advanced capabilities of the U.S. Navy and the support of American satellite and electronic intelligence services, Europe remains vulnerable. Although it formally possesses national navies, it lacks structured capacities for waging naval war and is therefore forced to adopt doctrines of asymmetric confrontation with the Russian Federation — similar to those employed by Ukraine.

BILLIONS FOR MINE WARFARE SYSTEMS

The countries of the Baltics, Scandinavia, and the Black Sea basin are not only aiming to modernize their existing fleets. On the contrary — they are preparing for total war through the mass mining of strategic waters and the creation of “drone armadas.” Large, vulnerable Cold War-era vessels are being replaced by robotic weaponry: anti-ship missiles, unmanned aerial vehicles, and crewless boats.

These war preparations are neither a political bluff nor a media fabrication. By 2027, the European Defence Fund has allocated €7.4 billion, of which €2.1 billion is designated for maritime drones, and €1.9 billion for naval mine warfare systems.

“The DM51 is a ‘smart’ mine of the 21st century. It turns the Baltic into a deadly trap for the Russian fleet.”

— Admiral J. Kaack, German Navy

We have already written in a previous article about the risks and strategic advantages of naval mines in EU military planning. This continuation focuses on European drone fleets.

TECHNOLOGY IS SHIFTING THE BALANCE OF POWER AT SEA

According to the plans of the European Defence Industrial Development Programme (EDIDP), European navies are expected to receive over 5,000 naval drones by 2026.

Why is this significant? Today, it is clear that the last two major naval conflicts — between Russia and Ukraine, and between Yemen and the United States — have shown what kind of weaponry dominates in prolonged and high-intensity wars. Fast, dispersed, and numerous combat units have the advantage — they either defeat traditional fleets or paralyze them, as in the case of Yemen (imagine — a country without a navy or military industry managed to neutralize the U.S. Navy during one year of conflict!).

These global trends in building military capabilities are not accidental; in the European context, they even have historical roots. European navies are undergoing a reorganization based on the ideas of total naval warfare, formulated by French Admiral Hyacinthe Théophile Aube. As early as the late 19th century, he developed the theory of confronting large naval fleets using fast, well-armed small warships.

Since the beginning of the Russia–Ukraine conflict, the Black Sea has become a testing ground for a new era of naval warfare — an era no longer dominated by battleships and aircraft carriers, but by small, yet deadly robotic systems. Ukraine, which did not have a traditional navy, managed to neutralize a significant portion of Russia’s Black Sea Fleet through the use of unmanned boats and missiles. That success has led to a reevaluation of centuries-old principles of naval strategy and renewed interest in the “Jeune École” theory — an asymmetric approach to naval warfare first proposed in the 19th century.

THE THEORY OF HYACINTHE AUBE

In the 1880s, French Admiral Hyacinthe Aube presented a radical idea: instead of investing in expensive armored warships designed for artillery duels, states should prioritize the mass deployment of small torpedo boats. His theory was ahead of its time — but was ultimately hindered by technological limitations. At the time, the torpedo boat was neither conceptually nor technically developed (no one even knew what the minimum tonnage for navigation should be). Installing a bulky steam engine into a small boat was far more difficult than into a large ship, and it would take another fifty years before turbocharged aviation engines for torpedo boats became available.

There were no computers for torpedo targeting — not even in theory. Targeting was done “by feel,” and the ships of that era faced major problems in detecting targets — radar wouldn’t exist for another 40 years, and even optical rangefinders weren’t widely used. The same year Aube became Minister of the Navy, France conducted large military maneuvers that ended in disaster for the theorists of the Jeune École. Due to bad weather, the torpedo boats couldn’t set sail for two days; the smallest, at 27 meters, stayed in base. Out of 12 boats of the 1st and 2nd class, only 5 made it to the port of Ajaccio — where they were supposed to attack a simulated enemy — exhausted by the voyage and incapable of launching torpedoes.

Moreover, the number of small boats Aube proposed cost nearly as much as building battleships. As a result, Aube was dismissed from his post as minister, and France returned to its traditional armored fleet.

PHILOSOPHY OF WARFARE

The Jeune École was much more complex than it is often portrayed: it represented a full philosophical concept of a new type of warfare. Its ideas were later adopted by the Germans, Japanese, and Soviets. Essentially, it was the smartest strategy ever devised for fighting a thalassocracy (rule of the seas). In his programmatic work, Aube presented the following logic:

- When the technologies of opposing fleets are equal, victory belongs to the side with numerical superiority and that does not commit reserves in the first phase of the battle.

- From this follows that the initiative in battle is always taken by the larger fleet, because the smaller one — all other things being equal — is doomed to defeat.

- Since the balance of forces is known even before the war begins, sea dominance will go to the stronger side without a fight.

- Because large naval battles are fought solely to establish control of the sea, over time they will disappear — and classical naval warfare will no longer exist as a form of combat.

HUMAN FEAR – THE NEGLECTED FACTOR

In the 20th century, torpedo boats from World War II and missile boats from the Cold War era (such as the Soviet Komar, which sank the Israeli destroyer Eilat in 1967) proved that small forces can threaten even large warships. But the real breakthrough came only recently — with the emergence of remotely operated and autonomous platforms that eliminated the main weakness of “mosquito fleets”: human vulnerability.

One of the fundamental elements of any war is fear — specifically, the fear for one’s own life. War is waged by people; they initiate and sustain it. And yet, this human factor is often forgotten, treated as shameful or irrelevant.

But it is precisely that factor that drives the development of military skill and technological progress in warfare. The desire to survive has always pushed humanity toward finding new ways to strike from a distance — and to ensure the safety of the one delivering the blow.

Naval warfare is no exception. A battle between a fast, small, and lightly protected but well-armed ship and a large, armored warship is a battle lost in advance for the smaller one. The crew of that smaller vessel will always be under psychological pressure due to their slim chances of survival — regardless of how much damage they can potentially inflict on the enemy.

That factor hindered the development and practical use of mosquito fleets for decades. Few crews would dare attack a destroyer or cruiser and cold-bloodedly attempt an assault under barrage fire.

The situation changed radically after World War II, with the advent of a new class of weapons — anti-ship missiles. These gave new momentum to the development of mosquito fleets, leading to the creation of missile boats and small corvettes. Their greatest advantage was the ability to strike from a safe distance. (Example: the Israeli Eilat was sunk by boats that never even left the harbor in Alexandria.)

Still, the core idea — lives on.

UKRAINIAN EXPERIMENT: HOW ROBOTS TRANSFORMED THE BLACK SEA

In recent years, we have witnessed a fundamental shift in the balance of naval capabilities. This is not a coincidence — it is a reality and a fact. Robotic weapon systems, which do not require the physical presence of a human operator in the combat zone, represent a massive leap forward in the evolution of warfare — comparable to the introduction of the first anti-ship missiles (which, in essence, are robotic aircraft).

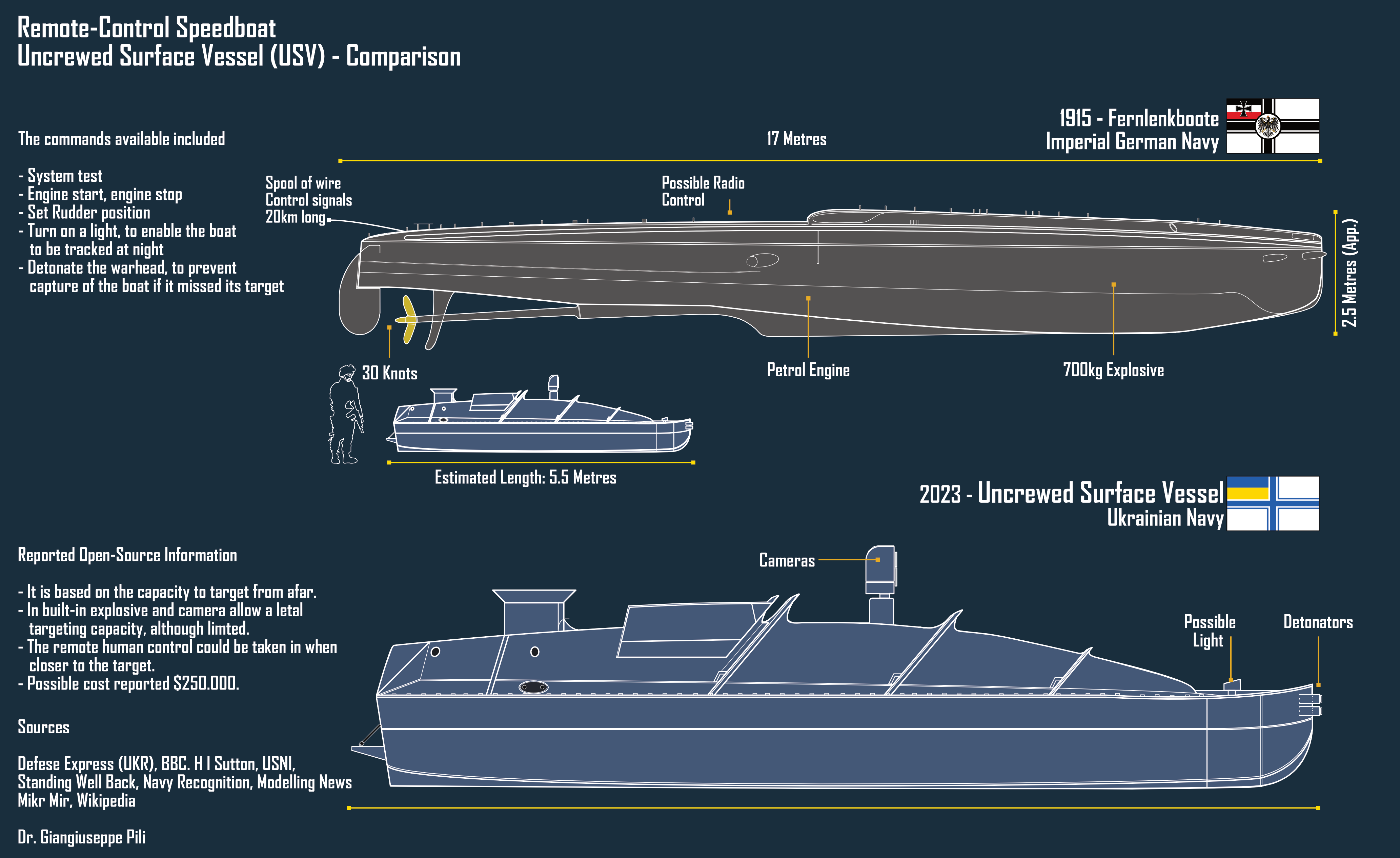

Until recently, however, robotization mainly applied to weapons, not to the platforms carrying them. Naval forces focused on developing missile systems and precision-guided munitions. But the conflict between Russia and Ukraine accelerated the emergence of an entirely new class of specialized naval vessels: Unmanned Surface Vessels (USVs).

On the Black Sea battlefield, these platforms have achieved unprecedented success — surpassing all previously known uses of “mosquito” fleets. Without exaggeration, we can say that we are witnessing a historic clash between robotic naval forces and a conventional fleet, in which remotely operated platforms hold the upper hand.

ASTONISHING SUCCESSES OF UKRAINIAN UNITS

Ukraine, having lost most of its fleet after 2014, placed its hopes in unmanned systems. The successes of its naval units have been astonishing. What are they based on? They can be summarized in the following key points:

• Unmanned Surface Vessels (USVs) cost dozens of times less than conventional warships but are capable of sinking frigates and corvettes.

• Network-centric warfare: NATO real-time intelligence allows Ukrainian operators to detect targets and strike without direct confrontation with Russian aviation.

• Psychological effect: even if a USV attack does not destroy a ship, it forces the enemy to remain constantly on alert and limits its freedom of maneuver.

As a result, by 2024, Russia’s Black Sea Fleet had lost several major vessels, including its flagship Moskva, and was forced to retreat toward the eastern coastal strip. The security of southern maritime routes — critical to the Russian Federation — now hangs by a thread and could at any moment turn into a full-scale disaster.

THE FUTURE OF NAVAL WARFARE

Robotization is an inevitable step in the continued evolution of naval weaponry. Until now, it has mostly encompassed aerial attack systems — especially missiles, with the process unfolding over several decades — but today we are witnessing the emergence of the first remotely operated naval platforms, which have rapidly progressed from prototypes to mass-produced and fully functional weapons.

We can clearly see that the ideas of French Admiral Hyacinthe Théophile Aube, first presented at the end of the 19th century, have been present throughout the entire history of naval warfare and tend to reemerge in every new phase of military technological development — precisely in the context Aube envisioned. First came the clumsy steam-powered torpedo boats, followed by the torpedo boats of World War II, then the missile boats of the Cold War’s golden age. In every case, we’ve seen both victories (even the early generations of steam boats achieved some success in World War I) and failures — stemming both from technical limitations (the difficulty of creating a vessel that is small yet fast, seaworthy, and deadly) and the human factor (few are mad enough to charge at 100 km/h in a 20-meter boat toward a 200-meter steel monster full of automatic weapons — and still cold-bloodedly complete the attack).

And now, finally, in the 2020s — 130 years after Aube’s death — his dream seems within reach. Unmanned Surface Vessels (USVs) remove the most vulnerable element of the “mosquito” fleet — the human. Now the entire space of the boat can be dedicated to fuel, weapons, and engines; the vessel can remain on alert for days without hunger, thirst, stress, fear, or fatigue, and ruthlessly strike any enemy force without concern for its own survival.

THE WEAKER SIDE DEFEATS THE STRONGER NAVY

The rules of combat are being fundamentally reshaped in real time. A small and lightly armed vessel can inflict devastating damage on capital ships thanks to aggressive and dynamic attack tactics — because the operator is no longer constrained by fear for their life. They risk nothing but the loss of a replaceable unit worth a few hundred thousand dollars — while they can cause damage worth tens of millions.

For the first time, the “mosquito” fleet has the opportunity to realize the vision Admiral Aube once had — a fleet of hunters capable of threatening much larger warships. Robotic naval platforms can operate effectively even when the enemy dominates the air — because, with proper technology and tactics, drones can hunt aircraft and helicopters just like ships. And we have already seen a battlefield that perfectly fits the doctrine of the “Jeune École” — where the weaker must defeat the overconfident navy of the stronger. This is a battle of doctrines and ideologies, of principles and intellect — capital ships versus the “mosquito” fleet.

But we must not overlook the complex ecosystemic structure that enables (and without which it would be impossible to achieve) the full potential of robotic naval warfare. Without a complete spectrum of reconnaissance capabilities, it is naïve to expect success from any number of unmanned boats, anti-ship missiles, or kamikaze drones. Weaponry is just one component of the armed conflict system — an important part, but not the decisive one.

Above all, what matters is the intellectual process: assessing one’s own capabilities, goals, and available means; conducting objective analysis of the enemy; setting realistic and achievable objectives; gathering and properly processing intelligence data. Only at the very end of that long and complex chain comes the direct strike against enemy forces.

ROBOTICALLY ARMED WAR IN THE BALTIC SEA IS A DANGER TO THE EU ECONOMY

Robotic weaponry — such as unmanned boats, naval drones, and autonomous mines — is making modern naval warfare more dynamic, decentralized, and destructive. If the conflict in the Baltic Sea escalates into an intense phase with the mass use of these technologies, it could have catastrophic consequences for the European Union’s economy across several key sectors. Active combat operations could paralyze vital trade routes — upon which the prosperity of the entire region depends — within just a few days.

The greatest threat lies in the cascading effect such a war could trigger. A blockade of maritime routes would hit the most vulnerable sectors of the European economy: energy supply chains would be disrupted, assembly lines in German and Swedish car factories would come to a halt, and logistics costs for the Baltic states would skyrocket. Of particular concern is the vulnerability of critical infrastructure — offshore wind farms, underwater cables, and gas terminals — the damage to which could trigger an energy crisis across the entire continent.

And this doesn’t even take into account the losses of European merchant fleets — which would undoubtedly be substantial.

Modern robotic naval systems, which have already proven their effectiveness in the Black Sea, now represent a fundamentally new threat to economies that heavily depend on maritime trade. The Baltic Sea — once a stable economic corridor — could quickly turn into a battlefield that paralyzes Europe’s logistical, industrial, and energy resilience.