The General Staff complex in the center of Belgrade was bombed during the criminal NATO aggression against Serbia and Montenegro (then the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia) in 1999 and was partially demolished for safety reasons between 2016 and 2017. The building was declared a cultural monument in 2005 due to the exceptional architectural work of Nikola Dobrović.

The declaration stated: “The complex is characterized by two monumental, terraced wings cascading down toward Nemanjina Street, thus creating an urban symbol of the city gate. The wings are set parallel to Knez Miloš Street and withdrawn from the regulatory line, approached through two dominant porticoes. In addition to expressive cascading forms, the facades are marked by the contrast of materials — robust, rust-red stone from Kosjerić, on which lie white, polished marble slabs from the island of Brač. The horizontal window strips on the facades, designed in the spirit of late modernism, represent a striking visual motif. The tower element, placed as a visual accent at the end of one wing (B), also dominates the silhouette of the entire complex. This cultural monument is the only and most complex realization of the respected modernist Nikola Dobrović, who occupies a special place in Serbian and broader Yugoslav architecture. Through its expressive form, urban composition, and the power of the ensemble situated at the crossroads of the city’s busiest streets, this architectural complex has become one of Belgrade’s most distinctive urban images.”

The protected status of the complex was revoked in 2024 — without explanation.

In November 2025, the Serbian Parliament is debating a law that would allow construction precisely on this site. Experts in the field argue that demolishing the bombed structure is unnecessary and that reconstruction is feasible. The state, however, justifies the move by claiming that a memorial complex would be more appropriate than a ruin.

The planned project envisions the entry of private capital and a substantial investment. In essence, the memory of NATO aggression may remain — but only so that an American tycoon, presumed to be the investor, can build whatever he desires and, if benevolent, grant the conciliatory Serbs a small room as a reminder of Belgrade under the bombs.

“LIBERATING THE SPACE”

And so, once again, we find ourselves in a Rashomon-like situation — characteristic of the atmosphere that has long prevailed within the coordinates of neo-colonialism, which, since the year 2000, have become the permanent framework of life and thought in Serbia.

The debate in the National Assembly in early November 2025 revealed that the authorities are opting for a model in which the legal status will be adjusted to fit the investment, while a significant portion of the professional and cultural public warns that this would erase one of the few material traces of the NATO bombing in the very heart of the capital.

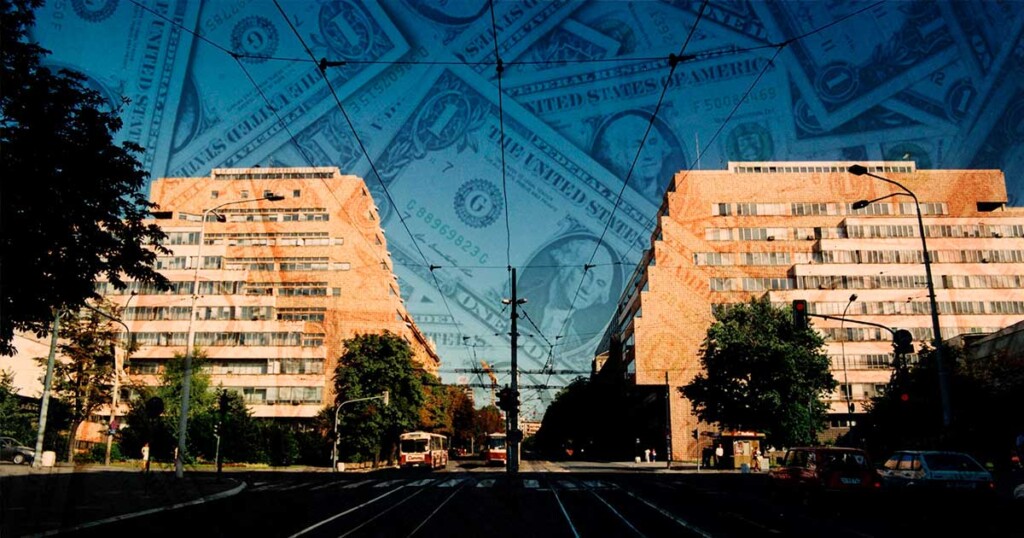

For more than two decades, the General Staff complex at the corner of Nemanjina and Knez Miloš streets has stood as an urban symbol of Serbian defiance — a reminder to citizens of their resistance to the world’s greatest military power. The current government now seeks to legally “liberate” Belgrade’s space from precisely such an object, which serves as a living reminder of the nation’s suffering and resistance.

In Parliament, a special law (lex specialis) is being considered, which would allow the land and ruins of the former General Staff building to be placed under a special-use regime — meaning that construction could proceed under a specific agreement between the state and investors. The authorities claim that the ruin is not a symbol of resistance and that a specially designed memorial complex for the victims of the 1999 NATO aggression is what Serbia truly needs.

Experts, however, argue that demolition is not technically necessary, as the dangerous remnants were already removed in 2016–2017, and that reconstruction and preservation of at least parts of Dobrović’s original architectural work remain entirely possible.

DOBROVIĆ’S ARCHITECTURE AND NEW MEANINGS

According to architectural experts, the building represents a work of high modernism from post-war Yugoslavia — a valuable testament to the creative spirit that followed World War II. Dobrović, as a creator, was a follower of philosopher Henri Bergson and his concept of intuitive “dynamic schemes.” But how did the architect “listen” to the philosopher?

Marko Matejić, who studied the Belgrade monument now slated for demolition, interprets the realization of “Bergsonism” in architecture by referring to the greatest Serbian “Bergsonian,” writer Stanislav Vinaver:

“Vinaver, among other things, writes: ‘To emphasize even more clearly the incompleteness of the initial intuition—the seed—Bergson later called it a sketch (a scheme). This sketch should be understood dynamically, as a set of dynamic tendencies within the seed itself,’ and continues by giving the example of a chess player who, while playing, ‘does not keep in mind the image of the pieces but their dynamic indications, the movement potential of each figure (for example, the rook is felt as something that moves in straight lines, the bishop in diagonals, the queen in both, etc.).’ According to Vinaver, the sketch, or the scheme, ‘is a germ that contains many moving directions and forces that, upon entering material life, define themselves more precisely through their own action.’”

The architectural work that, symbolically, became a target of the Western military alliance that sought to “bomb Serbia back to the Stone Age” stands as living proof that Serbian culture once followed the finest creative paths of the West. But the West did not care: by the end of the 20th century, it had transformed into a NATO predator, reviving its old Serbophobia from 1914 (when both Vienna and Berlin sought to crush Belgrade) and again in 1941, when Hitler ordered the bombing of the city at the confluence of the Sava and the Danube.

During the NATO bombing in 1999, the General Staff building was one of the most visible targets. It was struck in April and May, left partially standing but fully exposed toward Knez Miloš Street. Unlike other buildings that were quickly repaired after the war, the General Staff remained as a “wounded” segment of Belgrade’s main representative axis. Over time, this created a special layer of meaning: the building was not merely a ruin but a document of war — a spatial reminder that Belgrade, in 1999, was directly struck by the machinery of globalist evil.

THE “TRUMPIST TURN”

The key turning point occurred, let us recall, on November 19, 2024, when the Serbian government revoked the cultural monument status of the General Staff and the Ministry of Defense buildings. This decision provoked strong opposition from experts, as it contradicted the established view that the “wounded” structure could be reconstructed and integrated into the modern city without erasing its memorial function. It had been stated that the General Staff was protected not only as an individual building but also as part of the preserved architectural ensemble of Knez Miloš Street.

Now, in 2025, the authorities are taking things a step further by introducing a special law that would enable a prearranged investment project to be carried out on that very site. There is hardly anyone who thinks independently who does not see this as kneeling before the great business master — Donald Trump — and his son-in-law, Jared Kushner, a notorious power broker from the shadows.

Opposition MPs are demanding that the law be withdrawn, arguing that it represents a concession to big capital at the expense of the state’s own symbolic capital.

Supporters of the lex specialis insist that this is an investment that would combine commercial purposes (most likely a hotel-business complex) with a memorial segment. This hybrid model is typical of modern cities that seek to monetize attractive locations while simultaneously avoiding accusations of “forgetfulness.”

Architects involved in the debate publicly state that the building can indeed be reconstructed and that full demolition is not technically necessary. This means that the decision to demolish is political and economic — not architectural or structural.

MULTIPLE SYMBOLISMS

Dobrović’s architecture stood as a symbol of modern Yugoslav statehood and its military elite. The location, form, materials, and position along the Nemanjina–Knez Miloš axis reflected a state that saw itself as modern, militarily strong, and—at least officially—neutral.

The fact that the building remained visibly destroyed in the very center of the city transformed it into a spatial testimony to NATO’s aggression. For many Belgraders and their visitors, it was, in effect, an open-air museum. Cities rarely leave war ruins standing in their centers precisely because such structures continually evoke trauma. Belgrade, with the full moral right of a victim, made an exception—one that lasted for more than two decades.

Now, there is a push for everything that remains in the city’s spatial memory to be “reduced” and transformed into a memorial complex within a commercial project. The authorities claim that this would be a “greater symbol” than a mere ruin. Opponents of this “final solution” argue that the ruin itself was an authentic testimony, while the new complex, even with a memorial hall, would represent a “filtered memory” — remembrance adapted to business. It is a clash between authentic and staged memory.

THE VISIBLE SCAR

The General Staff building was the only major wartime scar along the route traveled daily by the state leadership (housing the Government, the Ministry of the Interior, and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs) — the same symbolic route taken by foreign delegations. As long as that scar remains visible, the state visually remembers 1999. Its removal, or its commercial humiliation, represents an attempt to redefine the state’s narrative: shifting from that of a “victim of aggression” to that of a “state of investments and reconciliation.” This is, in essence, a question of memory politics — or of amnesia, if one prefers.

Instead of allowing the visible mark of defiance against a stronger aggressor to remain — a mark guaranteeing that Serbs, if ever necessary, will again defend themselves by force — the defensive narrative is being relocated into protocol, ceremony, new buildings, and a rationalized professional army. Meanwhile, meaningless French Rafales are being purchased.

The fact that this law is being debated precisely when other issues concerning the abuse of the General Staff’s former cultural monument status are surfacing shows that the authorities want to “close the chapter” and prevent this issue from remaining a point of contention between urban planners, architects, and investors. The victims are to be forgotten — for, one way or another, a NATO future awaits. As always, we will lose ourselves and gain nothing.

The state has decided to move beyond the prolonged state of a “suspended ruin” and put this highly valuable space back into circulation. The struggle continues — between the memory of suffering from NATO bombs that fell as the Serbian Army defended Kosovo and Metohija, and the new staged symbol (a memorial within a business complex). Passing such a law is a signal that the decision will be implemented even without consensus from the professional public. The people, long ago, ceased to be asked anything.

With every step toward demolition, the state sends a message that it is willing to reshape even the most visible traces of 1999 if it deems it consistent with current “development” or foreign policy goals.

If Serbs wish to survive as a people of the Covenant, they must not sell or surrender their memory. Our eternal motto — even in 1999, when the “fairy from Košare” called out — remains: “For the Holy Cross and the Golden Freedom.” We were bombed, and still die from depleted NATO uranium, not so that the powerful of this world might buy our conscience and awareness, but so that we might remain what we truly are.

Anyone who thinks or acts otherwise has erased themselves from Serbian history. Thirty pieces of silver — even from Kushner — are not enough to quiet a guilty conscience.