The “Sandžak” project is deceitfully waiting for its five minutes of fame — and only the naïve could associate it with the fight against corruption, awning victims, justice, or a student election campaign. This is a project that has been smoldering beneath the surface of apparent peace in Raška for decades — and in the days to come, it threatens to fully reveal the true direction of its actions: territorial, legal, religious, and cultural secession. Astonishingly — amid the fog of student protests — it is the Serbs themselves, unaware of what they are doing, who are giving impetus to this project, taking on the role of co-creators in the establishment of an Islamic proto-state on the territory of their own country.

CIVIC EDUCATION INSTEAD OF NATO BOMBS

The “Republic of Sandžak” is an unfulfilled dream of the Muslim population dating back to the time of former Yugoslavia. After the wars ended, this process took a new, subtler direction — regional, yet transnational. Following the period between 2002 and 2013, during which most institutions in Novi Pazar, Tutin, and Sjenica were effectively removed from the Serbian identity space, came a phase of tactical evolution.

This time, the enemy took a different path — instead of NATO bombs and the creation of terrorist units, other methods were employed to reshape the state: civic education projects, multicultural dialogue, public discussions about “discrimination,” gender equality, and human rights. Under the guise of tolerance, the dismantling of Serbian cultural — and more importantly, institutional — presence in the Raška region continued at an accelerated pace.

Alongside the generous support of EU funds, GIZ, foundations such as Konrad Adenauer, the Open Society Foundation, and Western embassies, a decisive role in preparing the creation of a para-state was played by Turkey, through the TİKA agency — the official state agency of the Turkish government operating under the Ministry of Culture and Tourism and serving as the main instrument of Turkey’s soft power influence in the Balkans — and the Diyanet, Turkey’s Directorate of Religious Affairs.

MODELED AFTER SARAJEVO

Education has been recognized as the strongest tool of indoctrination. Following extracurricular activities that began back in the 1990s, the official school curriculum also started to shift — not in accordance with the majority population, but rather to align with the allegedly “more vulnerable,” yet in fact more aggressive, segment of the population, which, under the status of a national minority, introduces a program modeled after Sarajevo. Elementary school students are gradually transitioning to the “Bosniak language,” and history is being revised in a way that pre-narrative stories are now taking the shape of official history. NGOs from Belgrade actively organize numerous workshops, public discussions, and training sessions with lecturers from Priština, Tirana, and Sarajevo. Serbian state institutions are completely ignored — except, of course, when it comes to the budget.

Parallel to this, in public discourse, the adjective “Serbian” is being removed, and the term “Raška” is no longer used — only “Sandžak.” Terms such as “Sandžak or Bosniak culture,” “Sandžak or Bosniak youth,” “Sandžak business sector” are increasingly common, while certain media outlets and local officials have even stopped using the term “Serbia” in an institutional context, referring instead to “the state” in the third person — as something external and imposed.

INSTITUTIONAL TAKEOVER OR SILENT BUILDING OF A PARASTATE

After the first phase — from 2000 to 2013, following the October 5th changes — carried out a basic deconstruction of Serbian identity in education and public space, a new, much subtler but more effective phase began from 2014 onward: the internal takeover of institutions. Even in this phase, there was no need for violent methods. Instead, the system was undermined from within — through legislation, projects, and ultimately, the civil sector supported by both Western and Eastern intelligence services.

The key shift in the approach of foreign actors toward the Raška region occurred in 2014, when the formal implementation of mother-tongue instruction (including Bosnian) was introduced as an elective subject in primary and secondary schools, within a pilot program. The bilingual teaching program in Bosnian and Serbian in Serbia — especially emphasized in regions like Raška, the Autonomous Province of Vojvodina, and the far south of Serbia — was formally aligned with the legal framework and the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages, ratified by the Republic of Serbia in 2006.

That same year, the EU Delegation, the British Embassy, and the German development agency GIZ launched and supported a series of initiatives and projects focused on “dialogue and inclusion” in the region. Within these programs, local NGOs were engaged, including Urban In, Forum 10, the Sandžak Committee for Human Rights, the Muslim Youth Forum, the Igman Initiative, and a range of other subcontractors.

HOW THE BOSNIAK NATION WAS FORGED

Although the official goals — as is usually the case in such projects — were framed around strengthening democratic capacities, in practice these projects functioned as a platform for shaping the Bosniak cultural and political narrative in the region.

The introduction of content glorifying Islamic and Ottoman history into school programs was accompanied by teacher training, and under the umbrella of “interculturalism,” the “Bosniak nation” was forged. Officially formed in 1993, just 20 years later it already had its own language, a history over 1,000 years old, its own kings, heroes, and monuments.

That’s when TİKA and the Diyanet Foundation stepped in. At first, they did not challenge Serbian historical narratives directly — instead, under the guise of culture and the right to religious expression, they began restoring existing, and more importantly, constructing nonexistent monuments and religious structures throughout the Raška region. Thus, overnight, Novi Pazar, Tutin, and Raška were flooded with commemorative plaques, monuments to Ottoman heroes, and minarets.

As a logical continuation of this regional transformation, school and street names began to change, while monuments “offensive to Bosniak sentiments” were removed.

AXIS: TURKEY – SARAJEVO – TIRANA

In the media space, state media regulation is almost entirely ignored. Local radio and TV stations often operate without licenses or under the guise of cultural and religious centers. The content is highly exclusionary — dominated by news from Turkey, Sarajevo, Tirana, and the Islamic world, while national news from Serbia is relayed with irony, censorship, or openly ignored. The narrative remains consistent: Serbia is a foreign occupier, Belgrade is an illegitimate authority, and Sandžak is an “endangered entity” that is “seeking its place in Europe.”

At the same time, the administrative leadership of Novi Pazar, Tutin, and Sjenica is increasingly dominated by party activists from the SDA Sandžak led by Sulejman Ugljanin and the Justice and Reconciliation Party of the late Muamer Zukorlić. The politicization of local administration is a crucial step, especially considering the programs of these political organizations, which openly advocate for autonomy or a so-called “special status for Sandžak” within the Republic of Serbia.

Religious influence is growing in parallel. The construction of new mosques, funding from the Diyanet, Arabic language courses, the arrival of imams from the Middle East, theological scholarships, and logistical cooperation with educational institutions in Ankara and Istanbul all serve the goal of strengthening Bosniak identity.

These Diyanet and TİKA projects are not limited to the Raška region. The portal Vaseljenska recently reported on numerous projects being implemented across the Balkans — from Tirana, through Peć, Uroševac, Priština, the Raška region, all the way to Sarajevo. This phenomenon of “spiritual culture” through which Turkey builds influence is far more dangerous than NATO bombs, even though Turkey itself is considered an extended arm of NATO with an Islamic character.

Alongside all this, expressions such as “occupied Sandžak,” “annexed Novi Pazar,” or “illegal Constitution of Serbia” have become commonplace in public discourse — not on the fringes, but in mainstream media, and especially at workshops organized by NGOs from Belgrade such as the Youth Initiative for Human Rights, the Open Society Foundation, the Helsinki Committee for Human Rights, YUCOM, and others.

WAHHABI CELLS, TRAINING CAMPS, AND ISLAMIC EXTREMISM ON THE BORDERS

While Serbia has spent the last three years preoccupied with protests organized by the pro-Western opposition and NGO sector, something far more dangerous is taking shape in the rural parts of the Raška region, just a few kilometers from the administrative boundary with Kosovo and Metohija and the border with Montenegro. Secret Wahhabi cells, logistical networks, and training camps are forming, all bearing the hallmarks of terrorist readiness. Ostensibly religious camps in villages such as Žabren, Baćevo, Požaranje, and Brnjak are not merely expressions of religious fanaticism — they represent key flashpoints for a future security crisis in the region.

In March 2007, police discovered a camp about thirty kilometers from Novi Pazar, in the village of Žabren on Mount Ninaja. The camp consisted of several tents and a cave where members of a Wahhabi terrorist group were undergoing training. At that time, the police arrested Mirsad Prentić (1977), Fuad Hodžić (1974), Vahid Vejselović (1984), and Senad Vejselović (1983), all from Novi Pazar, while one member of the group managed to escape during the operation, according to a statement from the Ministry of Interior. A large quantity of plastic explosives, weapons, and rifle ammunition of various calibers was also found.

JIHADISTS OR RELIGIOUS ACTIVISTS?

According to a report by freerepublic.com, the Wahhabi movement first appeared in the Balkans during the civil war in Bosnia from 1992 to 1995, when thousands of mujahideen fighters from Islamic countries came to fight alongside local Muslims. Many remained in the country after the war and, according to foreign intelligence sources, indoctrinated local youth and even ran terrorist training camps.

A 2007 report also states that more than 3,000 Wahhabis attended the funeral of one of the movement’s prominent leaders, Jusuf Barčić. The report further mentions the existence of primary schools for Wahhabis:

“In Maoča, near the Bosnian town of Brčko, the Wahhabis even have their own primary school. ‘The ministry neglected these facilities. We renovated them with our own money and now educate our children here,’ said a teacher at the school, Nusret Imamović. About 20 pupils attend this school, following the Jordanian rather than the Bosnian curriculum,” Imamović said.

Terrorism experts believe that Wahhabis in the Balkans are secretly financed by Saudi “charitable organizations.” According to intelligence sources, five of the 9/11 attackers had previously served as Wahhabi-sponsored fighters in Bosnia. Dozens of other militants arrested in Pakistan, Afghanistan, Iraq, and Chechnya — proven to be members of various militant groups — were granted Bosnian citizenship.

Although Saudi Arabia allegedly invested in the construction of mosques and supported Wahhabi missionaries, only around three percent of the Bosnian population has adopted this more conservative form of Islam. Commentators like Muamer Zukorlić have claimed that Wahhabis remain a small group without significant influence in the region. The Wahhabis themselves insist they are merely religious activists.

RADICALIZATION THEN RECRUITMENT

Dževad Galijašević, a leading expert on Islamic terrorism in Bosnia and Herzegovina, Kosovo and Metohija, and the Raška region, has repeatedly warned in his reports and public appearances about the long-standing network of Islamist Wahhabi training camps. According to both his claims and intelligence reports, these camps are especially active in rural and poorly monitored areas, such as the villages around Tešanj, Maglaj, Bužim, and Goražde in Bosnia and Herzegovina, as well as the regions surrounding Uroševac, Prizren, and Đakovica in Kosovo and Metohija. During and after the 1999 war, a network was formed there, ideally suited for creating paramilitary units under the guise of religious communities and humanitarian organizations.

Galijašević claims that these camps serve for indoctrinating youth, weapons training, simulated combat scenarios, and preparing volunteers for deployment to foreign battlefields such as Syria and Iraq. He places special emphasis on para-jamaat communities that operate outside the framework of official Islamic institutions and which, according to him, have become “the infrastructure of Islamic terrorism” in the Balkans. These camps often have no visible markings, are hidden in forested areas, and rely on closed and encrypted communication channels.

The financing of these camps, according to Galijašević, comes from multiple sources: directly through Islamist charitable organizations from Saudi Arabia, Qatar, Turkey, and Iran, as well as through diaspora networks and legally registered NGOs operating in the region. He warns that many of these organizations act under the veil of religious and humanitarian missions, while in reality, they facilitate radicalization, recruitment, and provide logistical support to potential terrorist cells. Galijašević emphasizes that the West, by ignoring these developments, has enabled the creation of a continuous threat to regional security.

TRAINING FOR “SCOUTS”

Several analysts have warned about the existence of such camps within the Raška region as well. Although an official training site was allegedly dismantled, in August last year Sead Ramović — previously arrested during anti-terrorist operations targeting Wahhabi camps — was killed in a confrontation with the police. Weapons, a flag of an Islamist republic, and other materials pointing to radical Islamist activities were found in his apartment. This clearly indicates that Islamic radicalism is not only present but actively developing in the area.

Young people from Novi Pazar, Tutin, Sjenica, and surrounding villages regularly participate in camps now organized under the guise of hiking or religious education. However, it is no secret that these events involve a very different kind of training than what typical scouts receive. Main sponsors of these events include not only Western embassies and the European Union, but also Turkey’s TIKA and Diyanet, the Ensar Foundation (also from Turkey), as well as Saudi and Qatari foundations that channel funding through the diaspora and digital donations.

Despite clear evidence, Serbian police have their hands tied when it comes to intervening in these “religious-educational camps,” as any attempt at action is instantly labeled persecution of Muslims or a violation of religious freedom.

TURKEY, THE GREEN TRANSVERSAL, AND THE ISLAMIC BRIDGE AS A GEOPOLITICAL RECONFIGURATION OF THE BALKANS

Let us not forget that many Turks still refer to the Balkans as Rumelia — a term from the Ottoman legacy denoting a territory that was lost but never forgotten.

For nearly a decade now, a project has been unfolding below the radar — one with its own logistics, ideology, and geopolitical trajectory: the Green Transversal, an Islamic axis stretching from Istanbul, through Sarajevo, Novi Pazar, Pristina, and Tirana, all the way to the Adriatic.

This is not a conspiratorial myth — the term first appeared in analyses by Western intelligence agencies in the 1990s as part of a projection of an Islamic belt across the Balkans. Today, three decades later, it is taking on a tangible form.

At the very heart of this route lies Novi Pazar — geographically positioned as the connector between Sarajevo and Pristina, and culturally as the strongest reservoir of Islamic identity within Serbia.

Beyond TIKA and Diyanet, a wide range of Turkish institutions and foundations operate as front structures for the implementation of the neo-Ottoman agenda in the Raška region. Under the guise of cultural cooperation and “brotherly relations,” TIKA invests tens of millions of euros into mosque restorations, the construction of schools, and so-called intercultural centers, while Diyanet — Turkey’s official state religious authority — assumes personnel control over the Islamic Community in Serbia, sending imams for training in Istanbul and Bursa. Foundations such as Ensar, Yunus Emre, and Maarif act as extended arms of Turkish foreign policy, carrying out ideological engineering through educational, media, and academic channels.

The best illustration of all this is the collaboration between the Gazi Isa-beg Islamic High School (medresa) in Novi Pazar and Diyanet, through which hundreds of students are sent to Turkey to absorb Turkish cultural and religious models.

A CENTER IN ANKARA

In the town of Tutin, TIKA funded the complete renovation of the local municipal building, thereby gaining direct influence over local personnel policy. Today, Novi Pazar functions as the logistical, media, and political hub of Turkish influence in Serbia, hosting more than 15 organizations linked to Ankara, alongside Turkish businesses in the economy and media. The final symbolic gesture of this state-within-a-state dynamic is the planned opening of a Turkish consulate — a crown achievement of this strategic penetration.

However, in the Balkan context, Turkey should not be viewed solely as a military power. One must never forget that it is a NATO partner and, in this context, acts as an Islamized yet “acceptable” extended hand of Western interests. It leverages European values — religious freedom, minority rights, cultural autonomy — to embed its institutions deep within the heart of Serbia.

And if anyone believes there is a contradiction in the thesis that Islamic radicalism and Muslim separatist ambitions are simultaneously supported by both Turkey and the European Union, they need only look at Kosovo and Metohija — the most harmonious example of the joint operation of these two forces.

THE TRUTH IS MORE COMPLEX

Although the public believes that Serbia is “deaf” or passive in the face of increasingly evident security and cultural disturbances in the Raška region, the reality is far more complex — and dangerous. The state is not powerless because it refuses to act, but because its ability to react has been objectively obstructed — by internal blockades and external geopolitical blackmail.

The latest events in Novi Pazar clearly show that months-long blockades and the so-called student protests are merely a smokescreen for implementing the Republic of Sandžak project. Religious and racial slurs, chants like “This is Sandžak,” the waving of Palestinian flags, and the already-prepared “green fists” supported by the NGO sector — all of this should have triggered red alerts in any thinking observer.

The Vaseljenska TV portal and several independent sources have reported that in cases of extremism, attacks on police, and organized blockades, the prosecution refuses to act. Where responses have occurred, they have been limited to minor offenses, and following pressure on the judiciary, detained individuals were completely released. As a result, after eight months of intensive blockades, one political faction has developed a sense of impunity, and the parallel judicial system — rather than being an instrument of order — has become a shield for the blockaders.

FACTS LABELED AS HATE SPEECH

However, all this must be viewed in a broader context. In 2024, following numerous NGO reports and pressure from the pro-Western opposition, the UN General Assembly adopted a resolution declaring the events in Srebrenica as genocide. Despite the lack of any legal basis for such a decision — and the clear injustice it inflicted on Serbia — this act is now being used as justification for any future intervention, military or otherwise, should Serbia deviate from the prescribed Western course. Notably, the alleged genocide was committed against “Bosniaks.”

Simultaneously, domestic NGOs — such as the Youth Initiative for Human Rights, the Helsinki Committee, the Belgrade Centre for Human Rights, and local Sandžak organizations like Urban IN, Forum 10, and the Sandžak Committee — portray every police action, with the unlimited support of separatist and pro-Western media, as repression.

Any national media outlet that dares to report on Wahhabi camps, the ties between local authorities and foreign foundations, or the role of the NGO sector — now even within the blockader movement — is aggressively accused of spreading “hate speech” by pro-Western media using manipulative tactics.

If anyone still believes this is merely a “local misunderstanding” or “a form of pluralism within a shared state,” they should remember Kosovo in the late 1980s and early 1990s. That process began the same way — with demands for cultural autonomy, parallel education systems, institutional blockades, foreign support, and claims of repression by the majority state. Today, the Raška region shows the same symptoms — but this time, the mechanism is much more sophisticated.

And in the meantime, Turkey — through its NGOs and political channels — is quietly and steadily building a second state within Serbia.

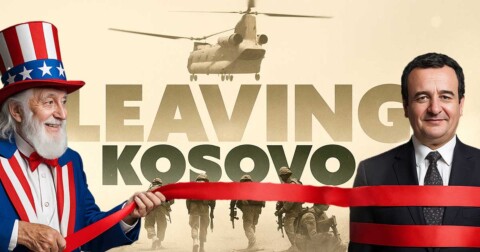

THE NEW KOSOVO

This situation not only resembles Kosovo and Metohija — it is the “new Kosovo.” Without barricades, but with blockades, t-shirts, symbols of resistance, and, most dangerously of all, with full support from parts of Serbian society that believe they are defending democracy, while in reality opening the door to a neo-Ottoman experiment.

Of all the frontlines currently opening in Serbia, the most dangerous one wears no uniforms and fires no bullets. It is a front where media, cultural institutions, and social networks are slowly, methodically, and precisely eroding everything that can be called the Serbian cultural code in the Raška region. What was once called “local news programming” is now a kind of media infantry serving ideological reengineering.

Behind every major media and social movement, there is always a network of people — not the ones seen at protests, but those pulling the strings behind the scenes. The same applies to the Raška region, but also to Bujanovac, Preševo, and Medveđa, as well as Vojvodina. What is today presented as spontaneous civic activism, student resistance, or regional rights to diversity, is in reality a networked structure composed of the civil sector, Western-backed activists, media operatives, and pro-Western politicians. All of them play a role, linked by grants, joint training programs, and ideological directives coming from abroad.

This is not some conspiracy theory. Every media house in Novi Pazar is partnered with an NGO. Every NGO is connected to a fund from Turkey, the United Kingdom, the United States, or Germany. And while our state continues to analyze what is “permissible” and what might provoke condemnation in a European Commission report — this network expands.