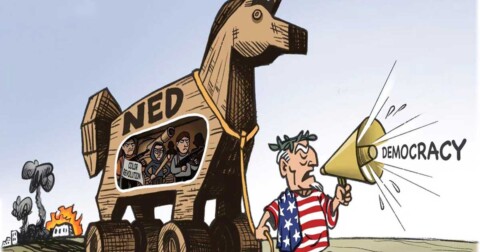

Rarely can a document — assuming it has the capacity to provoke geopolitical implications — be interpreted outside the context of the present moment and in isolation from other events, even if, at first glance, those events may not seem to be interconnected, as clearly demonstrated by the unfolding narrative of the student protests Serbia Brussels.

The trilateral declaration on military cooperation signed on March 18 in Tirana by Croatia, Albania, and the so-called Kosovo is followed chronologically by Croatia’s announcement of the introduction of mandatory military service, and then by a recently signed military agreement — also in Tirana — between Albania and the United Kingdom, which involves joint production of military equipment. Experience warns us that such a sequence of events is not coincidental and that it could, if not directly motivated by the Serbian question, be related to Serbia in the long term. This is also underscored by the fact that Serbia, currently focused on internal conflicts — whose instigators partly come from neighboring Croatia — is leaving the issue of reintroducing military service off the table, at least for now.

Unwise?

A REFUGE FROM “PERSECUTION”

The protests in Serbia, ongoing for the past three years and radicalized after the collapse of the canopy in Novi Sad, are, as the facts suggest, not a spontaneous Serbian phenomenon. More than Serbs themselves, at least in terms of logistics, Croats have been involved in their execution and organization. One of the main radicalizers of the most recent protest is Dinko Gruhonjić, a professor at the Faculty of Philosophy in Novi Sad — a frequent guest at panels in Croatia, a lecturer and agitator whose role in the NGO sector points to open cooperation with colleagues from the neighboring country. The fact that Professor Gruhonjić’s son is studying in Zagreb is a helpful detail in analyzing his ties with Croatians.

The protest held in Serbia on March 15 was seen as a trigger for a radicalization that could lead to riots and civil war. However, thanks to the Security Intelligence Agency and the swift response of the media, this scenario was avoided — though several individuals previously linked to Croatian intelligence services were arrested. Among those suspected of participating in the operation are Mila Pajić and her colleague Dorotea Antić, who, interestingly, were found with Gruhonjić in Dubrovnik on the day of the arrest — and have yet to return. The Croatian state, in fact, granted them refuge, citing what they claim is political persecution.

This is just one segment illustrating the cooperation between Croatian political actors and NGOs with Serbia’s pro-Western opposition. More precisely, this “partnership” predates the case of the two students, while the latest development continues a long tradition of security intrigues that Croatia has historically been prone to. In the current constellation, the logic is clear: Croatia is arming itself militarily while simultaneously doing everything possible to ensure Serbia buckles under the pressure of orchestrated unrest.

FROM MY VILLAGE TO BRUSSELS

However, just how far that support has gone was best demonstrated during the so-called student running tour to Brussels under the slogan “From My Village to Brussels.”

Even before the students who had previously cycled to Strasbourg returned to Serbia, a mega-plenum — composed of an unnamed group of individuals (perhaps even representatives of foreign intelligence services) and conspiratorially cut off from other protest participants under the pretext of protecting the organizational structure — announced a new plan: a trip to Brussels. This time, the students would run. Setting aside how humiliating this idea is — one that could only be embraced by a serf-like mentality accustomed to serving others and bowing to those who have systematically destroyed it for decades — this move was intended to stir empathy among politically unaligned Serbian citizens and to pave the way for the students’ demand to dissolve the Government of Serbia and call new elections. In this scenario, they, as a “new force,” would replace the worn-out pro-Western opposition, which has lost the people’s trust and is unable to regain it.

What stands out in this “run to Brussels” is the choice of the route — but even more so, the logistics: accommodations, travel organization, and receptions across Europe. Part of this was provided by the Croatian state, but the greater part was organized by a Croatian organization.

WELCOME TO A CITY WHERE NO SERBS REMAIN

The students set off from Novi Sad on a relay marathon heading toward Osijek, which was the first stopping point. On Vatroslav Lisinski Square in Osijek, they were welcomed by Croatian students from the “Student with Student” Initiative. The humiliating nature of this action is further underscored by the fact that the students were welcomed exclusively by Croats — as there are no longer any Serbs in Osijek.

The hosts unanimously described the event as a major gesture of reconciliation and a step toward the final revision of history, suggesting that at least the younger generations will have the courage to acknowledge the shameful crimes committed by the Serbian army against the residents of this city — a city that even the most cunning revisionists cannot absolve of the historically confirmed crimes adjudicated by international courts. Even Croatian courts sentenced General Branimir Glavaš for horrific crimes committed against Serbs in this city.

The next stop was Virovitica, where the students were welcomed by Croatian pop star Severina, an event met with mass enthusiasm. At the same time, in Serbia, that same day marked the commemoration of the breakout of prisoners from Jasenovac — the largest concentration camp in the Independent State of Croatia (NDH), where over half a million Serbs, Roma, and Jews perished.

SHAME OF SERBIAN FLAGS

The city of Varaždin independently organized a reception for the student protesters from Serbia. Namely, the Varaždin municipality covered the costs of the welcome and accommodation. What stood out throughout the Croatian leg of the tour was the complete absence of Serbian flags. Instead of national symbols, the participants opted for imagery of bloodied hands — presumably to avoid offending their hosts, who, like pop singer Severina, promote the narrative of genocide in Srebrenica and claim that Serbs were the only ones who committed crimes against other peoples — all this being said from an ethnically cleansed Croatia, free of Serbs. The excessive politeness of these young Serbs, who until recently marched through Serbian cities carrying symbols of their nation’s history and identity, apparently dictated that even the breakout from Jasenovac should go unmentioned.

After leaving Croatia, they were greeted in Austria by the Croatian diaspora. In Graz itself, the event was organized by the Croatian student community, notably including a group from the Department of Slavic Studies.

Between Vienna and Graz, one particular overnight stop drew attention: Oberpullendorf. A small town resembling a Vojvodina village, inhabited by Croatian emigrants. In Oberpullendorf, the students were met only by a team from N1 television at a parking lot. After giving statements to the media, the students were informed that they were permitted to spend some time in the main square — where it was also noticeable that the flags they had worn during their run had been put away.

CROATIAN EMIGRANT SUPPORT

What the pro-Western media following this Serbian student expedition failed to mention is that food and accommodation in this town were provided by a Croatian cultural cooperative based on the outskirts of Oberpullendorf, in the village of Veliki Borištof, called KUGA (https://www.kuga.at/hr/o-kugi/). According to statements given to the media by the hosts, this Croatian cultural association promotes Croatian culture and connects Croats in the diaspora. The reason they agreed to host the Serbian students, they say, was the request of an unnamed former Croatian student from the Department of Slavic Studies, who explained that it was important to offer hospitality to the Serbian students (https://vaseljenska.net/2025/05/03/od-varazdina-do-brisela-kako-hrvatska-sluzba-preko-kulturnih-centara-i-fakulteta-usmerava-srpske-studente/).

Despite Vienna being the Austrian city with the highest number of Serbs, barely 200 people showed up to greet the students — and among them, very few were Serbian. What stood out, easily noticeable from conversations with those present, was that most of the attendees had left Serbia in the early 2000s, during the DOS regime. By their own admission, they are unfamiliar with Serbia’s political situation, do not follow developments there, and yet still believe “change is necessary” — although they cannot explain why. Many of those present are not even from Serbia, nor have they ever lived there.

A NEW YUGOSLAVIA, AND OLD CROATIAN ASPIRATIONS

Alongside this eclectic crowd, there were also youths from a so-called revolutionary communist party led by a young Croat, waving flags of Communist Yugoslavia. At the same time, accompanied by Austrians, the student protesters were greeted by Austria’s Minister for Foreign and European Affairs, Beate Meinl-Reisinger. She gave a speech at the gathering, stating that the students heading toward Europe represent “a future that Austria respects and values.”

However, the most striking impression was left by the group of Croatian students who accompanied the Serbian runners from Osijek to Vienna, and eventually to Brussels. They did not spontaneously gather to support some distant Serbian students — their actions were logistically coordinated by the Croatian state and Croatian academic circles in the diaspora.

One of the key figures behind this organization is Professor Ivan Rončević, from the Department of Slavic Studies in Vienna — a Croat originally from Osijek. Speaking openly to the media, Rončević expressed his support, discussed his influence over the students, and emphasized the importance of the Serbian students’ journey to Brussels. He stated that, together with his students (whom he directed investigative media reporters to), he had been working on research papers exploring the geopolitical context of the Balkans in terms of reconciliation and the path toward building a new Yugoslavia — one in which, naturally, Serbia would make the greatest sacrifice at the expense of its national interests. As Rončević said himself, “the greatest threat to reconciliation and good relations is the nationalism of Serbia’s ruling regime.”

THE SYMBOLISM OF THE DATE

It is a bitter fact that the Serbian students arrived in Vienna on the eve of one of the most tragic crimes committed against Serbs in recent history. During the criminal military operation Bljesak (“Flash”), 283 Serbs were killed and over 15,000 were displaced. Croatia celebrates that day as a national holiday, while Serbian students — perhaps unknowingly — contributed to a revision of history that turns victims into perpetrators and globally recognized perpetrators into victims. It is also telling that the entire journey to Brussels was closely tied to the Department of Slavic Studies, revealing the Croatian background behind the entire operation. From Graz, through Vienna, all the way to Brussels, it was precisely the academic community from these Slavic Studies departments that played a key organizational role. These are not speculative theories but facts confirmed on the ground and through conversations with Slavic Studies students and Professor Ivan Rončević himself.

PICULA’S SATISFACTION — AS LONG AS IT’S NOT MOSCOW

In addition to the well-known Slovak MEP Vladimir Bilčík and Tanja Fajon — both familiar to the Serbian public for their anti-Serbian positions — the students received the most attention from Croatian MEPs Biljana Borzan, Predrag Fred Matić, and of course, the European Parliament’s Rapporteur for Serbia, Tonino Picula. Picula, clearly delighted with the Serbian students, expressed hope that this initiative would lead to reconciliation and recognition of the crimes committed by the Serbian people. He also noted that, at the moment, the only acceptable and promising path to the EU lies through the student initiative, emphasizing that Serbia’s president cannot simultaneously march in Moscow’s Victory Day Parade and claim to pursue EU integration.

Alongside the symbolic dates chosen for the trip to Brussels — such as the Jasenovac prison breakout and the anniversary of Operation Bljesak — it is notable that on the very day the students arrived in Brussels, Moscow held its annual Victory Day Parade over fascism. This fact was acknowledged by Martin Hojsík, Vice-President of the European Parliament, who remarked that “Pump it up – European Serbia”, and noted that the students’ journey, now crowned with a new “zero demand” — the call for new elections — clearly demonstrated their chosen direction. In his words, “The students are in Brussels — not marching to Moscow”, which clearly marks their political ideology.

THE ZERO DEMAND

Although the protests — and later the student blockades — were publicly presented as a nationwide uprising, primarily as a rebellion of the youth, the final outcome of the run to Brussels was the students’ “zero demand”: a call to hold new elections. To anyone even mildly familiar with the political climate in Serbia, it was clear from the beginning that the protests would culminate in exactly this. Yet the historic declaration came — symbolically — from Brussels, as if it had been waiting for someone’s approval.

Almost on cue, all pro-Western opposition parties and NGO movements stepped back, agreeing to hand over all their capacities to the students, while they themselves would withdraw entirely, making room for this supposed “new” political force.

However, the protests have not stopped. As the students themselves stated, they have entered a “new phase of struggle.” One part of that phase is the demand for the release of individuals accused of violently undermining the constitutional order and attempting to incite civil war. Among the accused is a newly minted heroine — Marija Vasić, professor of sociology, close friend of Dinko Gruhonjić, former wife of Nenad Čanak, and mother of Milan Čanak, a vocal advocate of separatism, independence for Vojvodina, and recognition of the so-called Kosovo. She is also a member of the “Movement of Free Citizens.” This demand aligns with the agenda of the ideologue behind the student political initiative — Tonino Picula — who also helped secure refuge for the two female students currently under warrant.

Although the protests are losing momentum, they are unlikely to stop entirely — which may not be a bad thing. They will ultimately expose the true intentions of the opposition, which is attempting to rebrand itself and act from behind the scenes under the guise of a student movement. These protests will continue until the elections, having become a new form of election campaigning — and notably, the first proxy war in history that Croatians are conducting in Serbia without direct presence.